Mediterranean Sea : the one and only

To evoke the Mediterranean, is to summon up the extraordinary history of the great civilizations shaped on its shores over the centuries. But it also means facing up to its future, which is more uncertain than ever. The various pressures associated with its use, population growth, pollution and global warming are all threats to its future, global warming are all threats to its unique biodiversity biodiversity and the services provided by its ecosystems. Mobilizing the general public , as well as political and economic leaders , is an imperative, with one compass in mind: what science tells us.

The stakes are high: environmental, of course, but also economic, energy, tourism, food, diplomatic. .. The Ioceanographic Institute launches its Mediterranean program, to identify future challenges, define areas of work and encourage action. A program enriched by the ” Mediterranean Missions” led by the Monaco Explorations under the leadership of HSH Prince Albert II.

A BIODIVERSITY HOTSPOT

The Mediterranean Sea may account for less than 1% of the surface of the world’s oceans, it is nonetheless considered one of the world’s most remarkable ” biodiversity hotspots.

SHE ABRITES

Sources :

(1) State of the Environment and Development in the Mediterranean (SOED), Plan Bleu, 2020.

Crédit Photos : Globicéphales noirs et Raie Pastenage- Greg Lecoeur

Endemic species

19%(2), the average percentage of species endemic and therefore unique to the Mediterranean. In addition to Posidonia, these include the Nicene sponge-calice (Calyx nicaeensis), the Mediterranean gorgonian head (Astropartus mediterranea), the limpet (Patella ferruginea), the deep-water crab (Geryon longipes), the Mediterranean clockfish (Hoplostethus mediterraneus), the small labrid (Symphodus mediterraneus)…

Emblematic species

The Mediterranean is home to exceptional biodiversity, with emblematic species such as the Mediterranean monk seal (Monachus monachus), one of the world’s most endangered seal species, as well as the bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus) and the Mediterranean bluefin tuna (Thunnus thynnus), whose populations are crucial to the region’ s ecological and economic equilibrium.

Coralligenous drop-offs: oases of life

Coralligenous drop-offs in the Mediterranean are rich and complex underwater formations, made up of limestone structures produced by red algae. Located at depths of between 30 and 120 meters, these habitats are home to exceptional biodiversity, from gorgonians to sponges and numerous species of fish. Fragile and threatened by human activity, they play an essential ecological role for marine fauna.

Posidonia meadows: the prairies of the sea

Cetaceans

Around twenty species of cetacean live in the Mediterranean, including various dolphins, beaked whales and the fin whale, the second largest animal on the planet… They are often found in the Corso-Liguro-Provençal basin, particularly in the Pelagos sanctuary.

Sources :

2) SoED, https://planbleu.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/SoED_full-report.pdf.

(3) Repport “Projet Med-ESCWET”, MedWet, 2017.

DID YOU KNOW?

The name Mediterranean comes from the Latin Medius terrae which means in the middle of the land.

The Mediterranean is particularly sensitive to the effects of climate change. Sea surface temperatures have risen by between 0.3°C and 0.45°C per decade since the 1980s. Increasingly frequent heat waves – known as marine heatwaves – are having serious impacts: disappearance of coral reefs, acidification, major changes in precipitation patterns. Sea level rise (2.8 mm/year) could reach 0.5 to 1 metre by 2100(4), accentuating the risks of flooding, erosion and loss of coastal habitats. However, these impacts are also linked to political choices, such as land artificialisation, which reinforce vulnerabilities and create a vicious circle. Responsible governance remains essential to reverse this dynamic.

reached on August 15, 2024!

Source: Copernicus Marine Environmental Monitoring Service (CMEMS)

Demographic pressure...

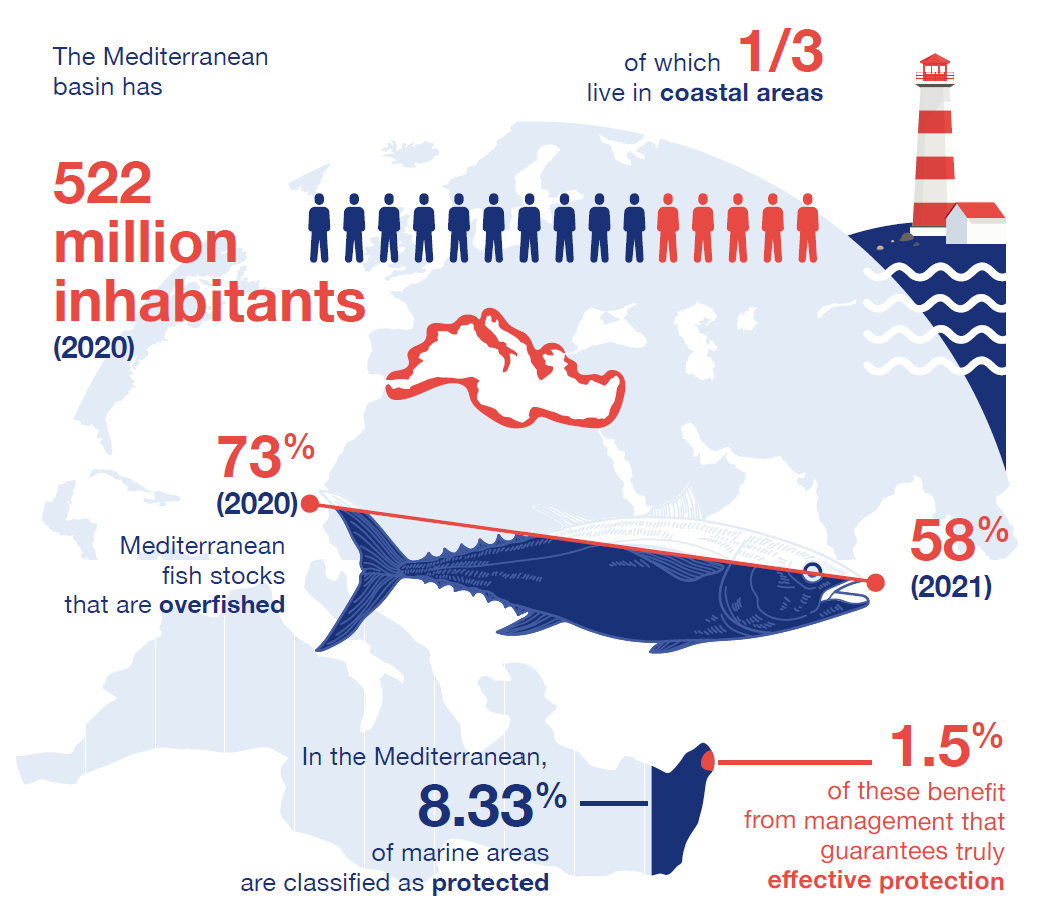

In the 1960s, the Mediterranean basin was home to around 239 million people(1). Forecasts predict that this figure could rise to 580 million by 2050.

One in three inhabitants lives in a coastal zone , This has led to the artificialization ofat least 40%(2) of the coastline. The associated risks for these populations are well known, whether in terms of flooding, erosion or soil instability. This demographic and urban pressure has direct consequences for coastal ecosystems: destruction of habitats, pollution linked in particular to the lack of infrastructure to treat wastewater…

...and economic challenges

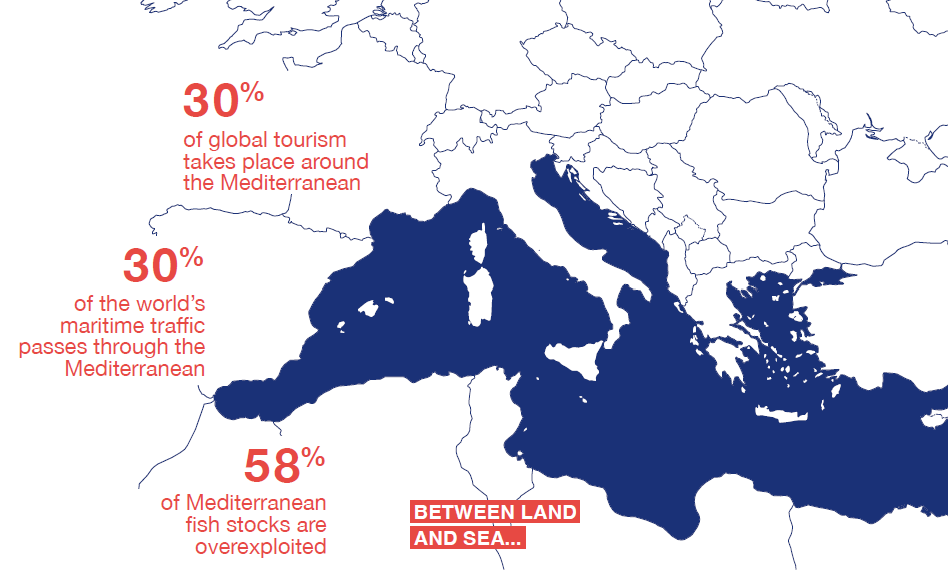

- Worldwide tourism 30% is concentrated in the Mediterranean(2).

- 30% of the world’s maritime traffic passes through the Mediterranean(2).

- Fishing 58% of Mediterranean fish stocks are overexploited(3).

Sources:

(1) Tendances et perspectives démographiques en Méditerranée, Plan Bleu Cahier n°21, 2020.

(2) State of the Environment and Development in the Mediterranean (SOED), Plan Bleu, 2020.

(3) The State of Mediterranean and Black Sea Fisheries, FAO, 2023.

(4) Mediterranean Assessment Report (MAR1), MedECC, 2020.

Photo credit: Posidonia Herbarium – Greg Lecoeur

Credit Photo : Hervia Pèlerine – Greg Lecoeur

A FRAGILE BALANCE

Preserving the Mediterranean means protecting a unique natural and cultural heritage, but also ensuring the economic and social resilience of its populations in the face of future challenges. Acting for this great sea means acting for our common future.

The challenges of overfishing and aquaculture

The overexploitation of fish stocks has two main causes: the steady increase in industrial fishing in recent years(40% of total tonnage) and the rise in illegal fishing. In a report dating from 2023, the General Fisheries Commission for the Mediterranean (under the aegis of the FAO), considered that 73% of Mediterranean fish stocks were overexploited. By 2021, thanks to specific regional fishing regulation measures

, this figure will have fallen to around 58%. While encouraging, these figures remain global and vary greatly from one species and region to another.

Scientifically-based quotas have been adopted to combat overfishing, but their effectiveness depends on their formal adoption and implementation by the relevant political authorities. When translated into concrete measures and effectively applied, these quotas can produce convincing results, as in the case of bluefin tuna. Furthermore, aquaculture, while offering an alternative to fishing, generates significant environmental impacts. For example, intensive sea bass farming exacerbates pressure on ecosystems, in particular by generating pollution due to waste and CO2 emissions.

The need for effective governance

The 30×30 target, officially adopted at COP15 of the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) in December 2022 in Montreal, is an international commitment to protect 30% of land and oceans by 2030. This agreement sets ambitious targets for combating biodiversity loss and restoring natural ecosystems. While this international objective is promising, particularly in the Mediterranean with its unique biodiversity, its effective implementation remains a challenge.

Governance in the Mediterranean basin is hampered by fragmentation and overlapping regional agreements, which complicate the coordination of conservation measures. The Barcelona Convention, the main agreement for the protection of the Mediterranean and the sustainable development of the basin, was adopted in 1976 and sets out ambitious commitments for its Parties. Unfortunately, it suffers from a lack of means to support their implementation and to sanction the signatory states’ failings. Beyond the Convention itself, the fragmented institutional framework of the many states bordering the Mediterranean basin, political and diplomatic challenges, disparities in resources, and the absence of strong legal constraints all hamper coherent and effective action.

From the maritime economy to the Blue Economy: a new impetus

"We must move forward in building a blue economy, so that we can continue to create the progress our contemporaries are demanding."

S.A.S. le Prince Albert II de Monaco Discours lors du Forum économique mondial, Davos, 2024

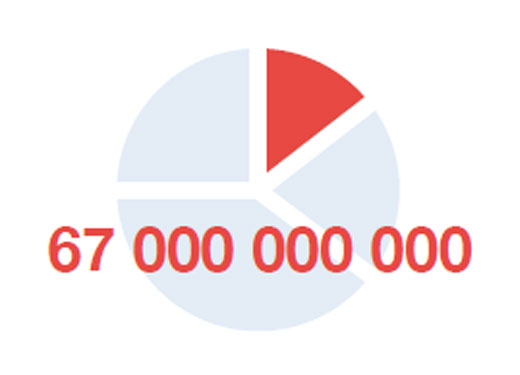

The blue economy is distinguished by its focus on sustainable practices, seeks to reconcile economic needs with the preservation of ecosystems ecosystems, and is therefore a response to these new expectations. In 2019, according to European Union data, the blue economy generated 67 billion euros in gross added value and over 2 million jobs(2). However, on the scale of the Mediterranean basin – with its 522 million inhabitants – these figures remain relatively modest, underlining an untapped potential.

However, this potential should not be exploited exclusively by coastal tourism, which already accounts for 61% of the gross value added of the blue economy, while fishing and aquaculture only contribute 7.5%(2). This raises a strategic issue: the need to diversify the blue economy. The COVID-19 crisis revealed the fragility of a model too dependent on tourism: when tourism collapses, more than half the blue economy falters. This vulnerability calls for a rebalancing of virtuous maritime activities, by strengthening other sectors such as small-scale fishing, sustainable aquaculture and marine renewable energies.

Investing in a sustainable blue economy and finance is not only a necessity, but also a strategic opportunity to ensure a prosperous a prosperous and resilient future for the Mediterranean and its inhabitants. The blueeconomy sectors thus offer remarkable potential for potential for innovation and wealth creation.

Sources :

(1) Rapport “Reviving the economy of the Mediterranean Sea” par WWF et The Boston Consultive Group, 2017.

(2) Chiffres 2019 parus dans “The EU Blue Economy Report”, 2022.

There is a significant gap between the maritime economy, which encompasses all economic activities directly linked to the oceans, seas and coastal zones, and the blue economy , which focuses on the sustainable management and use of marine resources in order to limit environmental impacts and maximize social and economic benefits.

If we were to calculate the wealth of the Mediterranean Sea in the same way as a country’s national GDP, it would rank 5th among the economies of the

basin.

The total value of economic production in the Mediterranean is estimated at 450 billion euros.

In 2019, the blue economy in the Mediterranean generated around €67 billion in grossvalue added (GVA)…

…and supported 2.05 million jobs.

THE PROMISE OF MARINE PROTECTED AREAS?

What is a Marine Protected Area (MPA)?

Marine Protected Areas (MPAs ) are maritime zones specifically designated to protect biodiversity, where certain human activities are restricted in order to preserve ecosystems and promote their regeneration. Although MPAs are essential tools, they do not solve all the challenges associated with the degradation of marine ecosystems. Indeed, they cannot compensate for the accumulation of threats. In this context, the main challenge for MPAs is to reconcile conservation and economic development, particularly in areas where human pressures are high. Their success thus depends to a large extent on management measures adapted to local contexts. Involving stakeholders in their creation and management is therefore essential. However, the effectiveness of MPAs is not limited to regulating activities within them. These areas remain vulnerable to external pressures, such as pollution, overfishing or the impacts of climate change. Consequently, their overall effectiveness also depends on managing interactions with neighboring areas and external dynamics. Although MPAs offer ecological, social and economic benefits, contributing to the resilience of ecosystems to natural disasters and supporting local economic activities, their effectiveness relies on a holistic approach that integrates these multiple factors.

In the Mediterranean, 8.33% of marine areas are classified as protected, but only 1,5% have a management plan guaranteeing truly effective protection.

Source: The 2020 status of Mediterranean marine protected areas, MedPan.

Did you say AMCEZ?

According to the Convention on Biological Diversity, Other Effective Conservation Measures by Area ( OECMA ) are defined as follows: “A geographically delimited area, other than a protected area, which is regulated and managed so as to achieve positive long-term positive and sustainable results for the in situ conservation of biological diversity, including associated ecosystem functions and services and, where appropriate, cultural, spiritual, socio-economic and other locally relevant values “.

Thus, AMCEZs are conservation tools that complement MPAs, s , with different practices and uses , but which contribute just as much to nature conservation. It is essential to value and recognize these initiatives, which are generally local, and the individuals behind them, in national conservation schemes.

DID YOU KNOW?

Cap Roux in the Mediterranean is an area protected by the fishermen themselves, who have set up a 4.55 km2 reserve to preserve fish stocks. Since its inception in 2015, this initiative has relied on community-based management practices, such as reduced fishing periods and prohibited zones. Managed by the local cooperative, the reserve has demonstrated notable success: an increase in the fish population, particularly of endangered species, and a strengthening of links between fishermen and conservation.

Variable levels of protection

According to the levels of protection defined by the MPA Guide, economic activities in MPAs vary according to their conservation objectives.

Activities such as sustainable fishing and aquaculture , responsible tourism and renewable energy production can be compatible with MPAs under certain conditions, can be compatible with MPAs under certain conditions. However, highly destructive activities , such as mining or oil and gas extraction , are incompatible with their conservation objectives.

Obstacles to good MPA management:

Lack of a harmonized universal framework:

❌ although the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) recognizes MPAs as an essential tool for conservation, it does not propose a universal definition specifying levels of protection or authorized activities. This leads to varying interpretations depending on the national or regional context. For example, MPAs with strict protections can coexist with areas where destructive activities are permitted, diluting their overall effectiveness.

Insufficient management plans:

❌ to be effective, MPAs require financial, human and technical resources to develop and implement appropriate management plans . In their absence , they risk remaining ” paper MPAs” , with little or no real impact on conservation.

MINIMAL

PROTECTION

Major extractive activities, such as industrial fishing and shipping, are permitted, although the MPA retains some conservation benefits.

MODERATE

PROTECTION

Economic activities, including larger-scale fishing and aquaculture , are tolerated, but can have significant impacts on the environment.

HIGH

PROTECTION

Limited activities, such as sustainable artisanal fishing or responsible tourism, are authorized under strict conditions to minimize impacts.

INTEGRAL

PROTECTION

No extractive or destructive activities are permitted , preserving the ecosystem in its natural state.

Source:

The MPA Guide, Defining MPAs and their level of protection.

The MPA Guide is a scientific framework designed to assess and understand the effectiveness of marine protected areas (MPAs). It was developed by a group of international experts including IUCN, National Geographic and the UN Environment Programme.