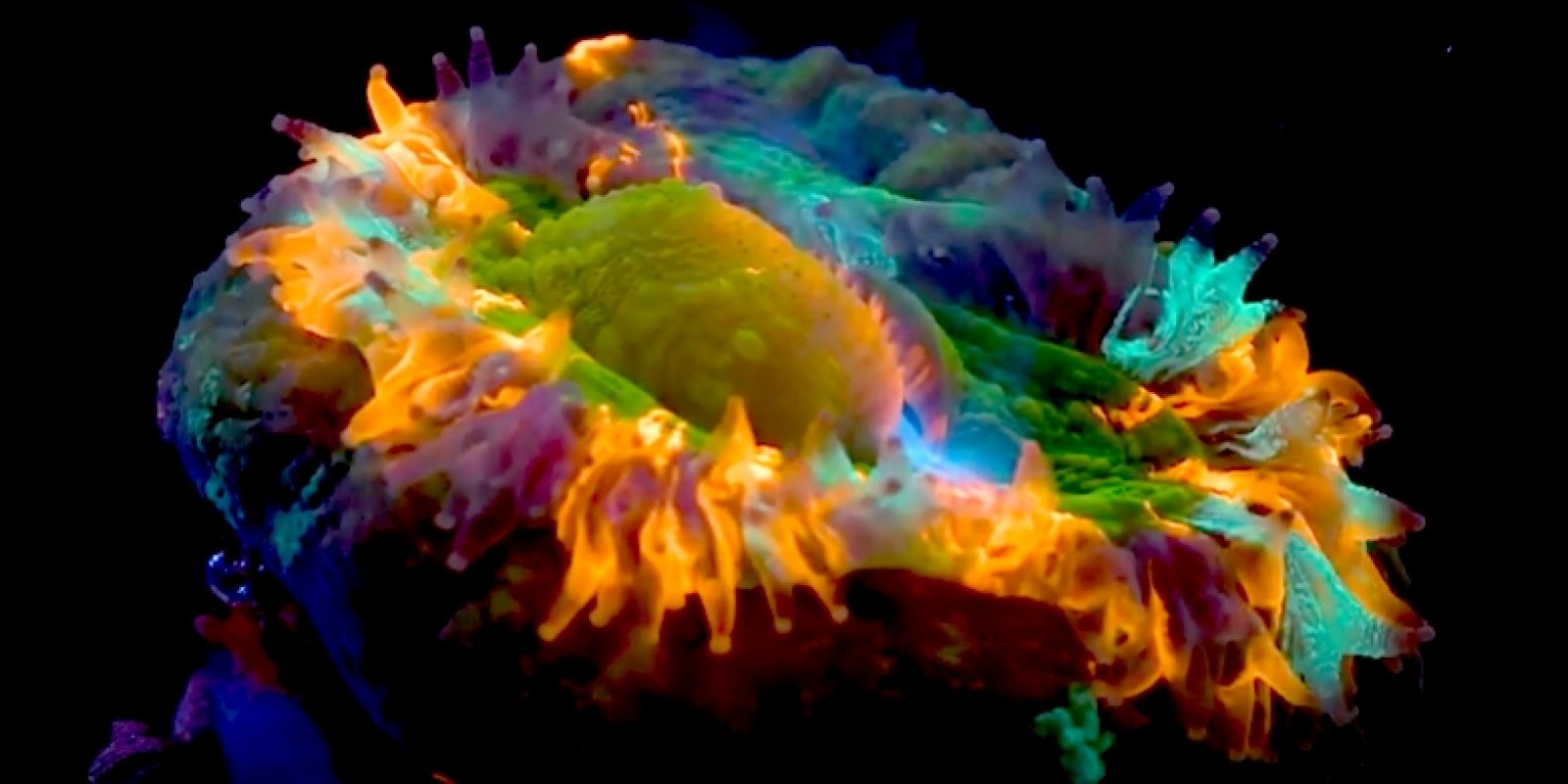

Coral, plant or animal?

For several centuries, the nature of this strange organism, resembling small flowering trees attached to rocks at the bottom of the sea, was the subject of much debate by naturalists.

Corals are in fact small animals, called polyps, in the shape of sea minnows that can form colonies. These polyps make a common skeleton which for some species become the foundation of a coral reef.

The first observations of coral were made in the Mediterranean, by Pliny the Elder (1st century AD) on red coral (the one from which jewellery is made). Once brought to the surface, the coral would quickly die. Thus, it was considered a sea plant that turned into stone when taken out of the water. It was not until the middle of the 18th century that it was recognized as an animal that was classified in the large family of stinging animals, the Cnidaria.

The different corals

There are solitary corals, colonial corals, reef builders, soft corals, false coral…

Not all corals build a calcareous skeleton, like hard corals. There are also soft corals which generally grow faster… And not all corals live near the surface in warm tropical waters, some live deeper and sometimes in cold waters.

For more information:

- Deep-sea corals in cold waters by Ricardo Serrão Santos, oceanographer

- Our factsheets on coral

Coral reefs

Coral reefs are made up of a multitude of coral species which together form an ecosystem, i.e. a very specific natural environment made up of different plants and animals.

Coral reefs are among the largest and most complex ecosystems on the planet. They are home to thousands of species of fish, but also other animal species, such as crabs, starfish, shellfish…

Coral reefs serve as refuges, food reserves and nurseries for their many inhabitants: from the smallest algae to numerous fish and invertebrates, but also to sea turtles and sharks.

For more information:

- Coral reefs by Jean Jaubert, marine biologist and former director of the Oceanographic Museum of Monaco

- Our factsheets on coral

Like all animals, coral reproduces sexually (by releasing sperm and eggs) but also asexually (by taking cuttings like a plant)! Let’s discover the mysterious reproduction of corals.

Sexual reproduction

Like all animals, corals reproduce sexually. There are male polyps that produce male gametes (sperm) and female polyps that produce female gametes (eggs). Corals that live in a colony can have both males and females in the same colony, so the coral is said to be hermaphrodite.

The fertilization that takes place during the meeting between the male and female reproductive cell can be of two natures: the fertilization is external, and the spermatozoids go to the meeting of the ovules in full water, after being ejected by the polyps. Fertilization is internal, the male polyps emit spermatozoa which are received in a female polyp incubator.

During fertilization, an egg cell is formed which gives birth to a ” planula larva ” that wanders for some time in the ocean currents before dropping to the bottom. The larva then transforms into a polyp which is fixed on a rock and becomes a new colony. Sexual reproduction allows the propagation of corals in new spaces while ensuring a genetic mixing.

Asexual reproduction

The coral, like other animals, has the particularity of being able to reproduce in an asexual way, i.e. without releasing sexual cells. Coral fragments, either because of natural disturbances (storm, cyclone or predator) or because of voluntary or involuntary human action. If the fragmented piece, which can be called a cutting, is in a favourable environment, it will continue to grow and form a new colony and thus strengthen the cover locally on the sea floor. It is this particularity that offers the possibility to aquariums to populate their tanks without taking species from the natural environment.

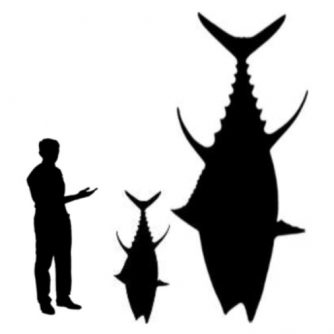

A record-breaking fish

The Atlantic bluefin tuna is a large marine fish and the largest in the “tuna” family. At the age of 30, it can reach 3 meters and exceed 600 kg! Its size and weight at maturity differ according to the geographical area. In the Mediterranean, it is adult at the age of 4 years (i.e. 30 kg for a length of approximately 120 cm) whereas it takes 9 years in the West Atlantic (i.e. 150 kg for approximately 190 cm).

"Small" or "big"?

In our collective memory, the size and weight that certain animal species can reach (crocodiles, sharks, large fish such as cod or halibut) have disappeared. In just one or two generations, we have hunted, fished, and eliminated the large individuals. What we consider today as “big” specimens, are in fact only “small” or “medium” ones! Atlantic bluefin tuna is no exception to this rule. A fish of 30 kg – a weight that is already quite substantial – is only a “baby” compared to large individuals of several hundred kilos!

In the Mediterranean basin, the Atlantic bluefin tuna has been exploited since the Neolithic period, as attested by the rock engravings in the caves of Levanzo Island, near Sicily (photo below, far right: it is a tuna and not a dolphin!).

It is also present on this Greco-Hispano-Carthaginian bronze coin (200 to 100 B.C.), originating from Gades or Carthago Nova, a Greek city in Spain. Coll. Oceanographic Institute.

A star of Japanese cuisine

Today, bluefin tuna is used to make sashimi and sushi for health-conscious Japanese consumers. Other tunas (skipjack, albacore, yellowfin) are used more in canned and other prepared and preserved products.

Premium bluefin tuna are reaching record prices. In January 2019, at the Tokyo New Year’s auction, a 278kg Pacific bluefin tuna (Thunnus orientalis cousin of the Atlantic bluefin tuna Thunnus thynnus), caught in northern Japan, was auctioned for an incredible 2.7 million euros!

Mediterranean tuna is exported...

In the Mediterranean basin, more than 20 countries exploit bluefin tuna, which makes it a highly shared marine resource that can only be managed within an international framework. Over the last two decades, 60% of the catches have been made by France, Spain, Italy and Japan, giving these countries a particular responsibility.

The vast majority of bluefin tuna caught in the Mediterranean by industrial fisheries is destined for aquaculture and the fattening activity that supplies the Japanese market.

Atlantic bluefin tuna

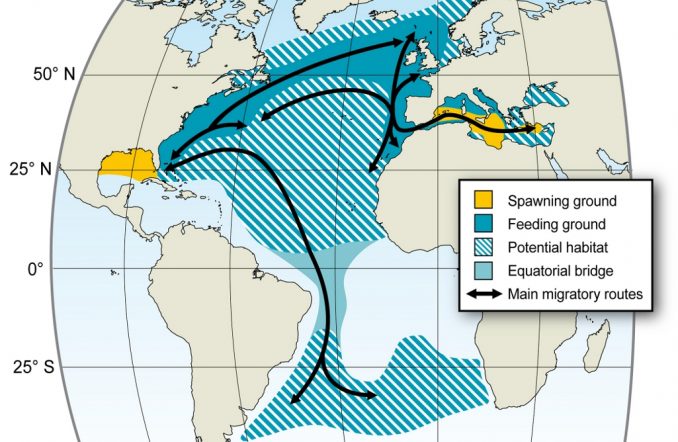

The Atlantic bluefin tuna (Thunnus thynnus) lives in the Atlantic Ocean, the Mediterranean and the Black Sea. It moves in schools and makes important migrations to feed and reproduce. Although it tends to live in surface waters, it can dive to depths of up to 1000 m. This voracious and fast predator (it is capable of speeds of over 100 km per hour) feeds on fish, squid and pelagic crustaceans (living in open water). A record-breaking fish, it can live for 40 years or more, reach 3 m in length and weigh 600 kg! Located at the top of the marine food chain, its predators are the killer whale, the great white shark … and Man!

Read more:

Find the IFREMER press kit on bluefin tuna

Geographical distribution of bluefin tuna

This map shows the spatial distribution of the Atlantic bluefin tuna: in blue its distribution area, in yellow the known spawning areas. The black arrows indicate the main migration routes (Figure adapted from Fromentin and Powers – 2005) © Ifremer.

Did you know?

The bluefin tuna is one of the rare fish capable of endothermy: it adapts its body temperature to its environment and can thus evolve in cold water (where it feeds) or warm water (where it reproduces), that is to say from 3 to 30°C!

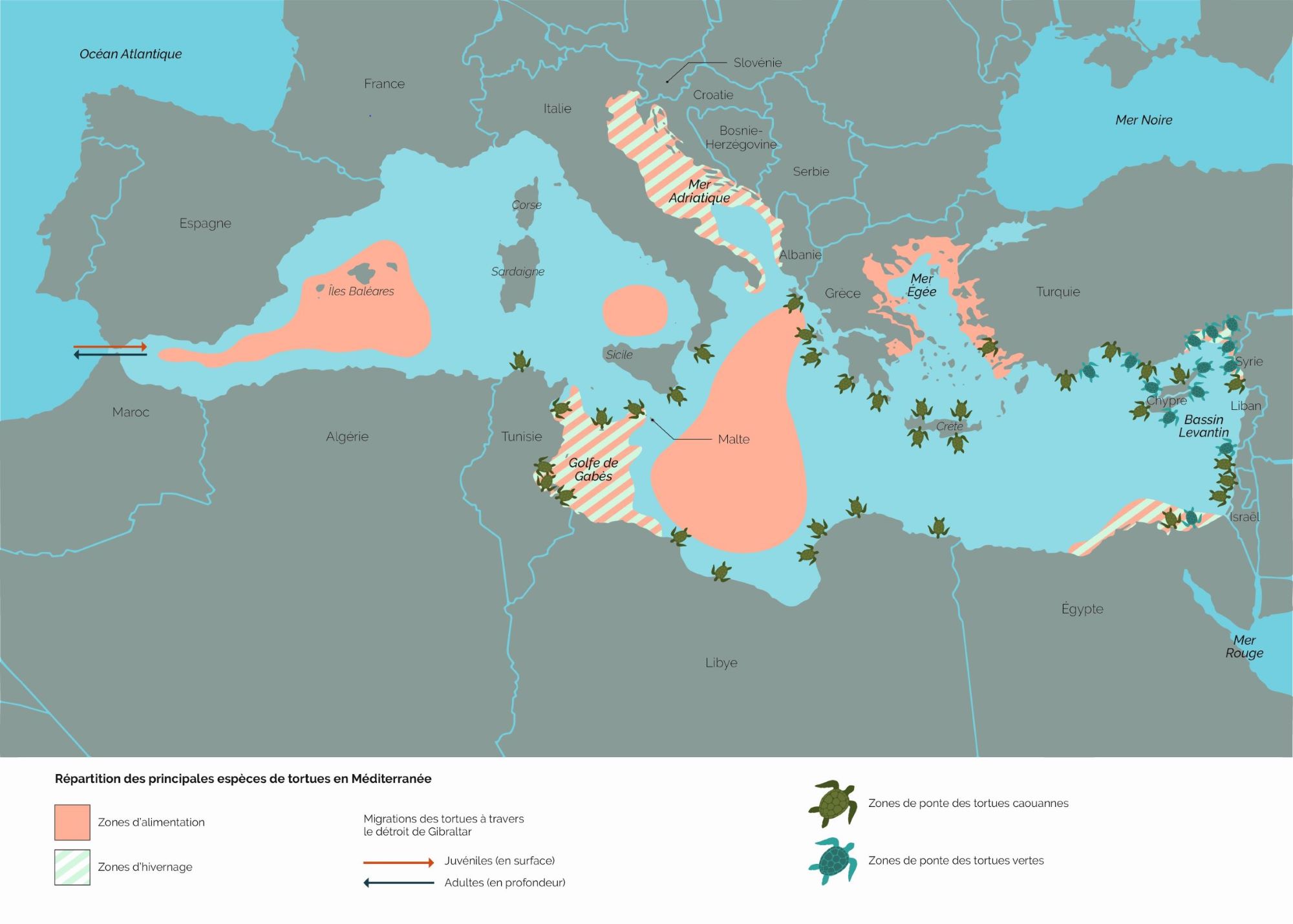

6 marine turtles are present in the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean has 46,000 km of coastline and covers 2.5 million km2 , or less than 1% of the total ocean surface. Well known as a global biodiversity hotspot, it is home to six of the seven species of marine turtles.

The loggerhead turtle Caretta caretta is the most common, followed by the green turtle Chelonia mydas and then the leatherback turtle Dermochelys coriacea, known to be the largest turtle in the world.

The rarer Kemp’s ridley turtle Lepidochelys kempii and the hawksbill turtle Eretmochelys imbricata have only been observed a few times in the Mediterranean to date.

In 2014, a stranded turtle was formally identified in Spain. It is the olive ridley turtle Lepidochelys olivacea.

An uneven geographical distribution

Loggerhead, green and leatherback turtles are found throughout the Mediterranean, but their distribution is uneven depending on the species and the time of year.

The loggerhead occupies the whole basin but seems to be more abundant in the western part, from the Alboran Sea to the Balearic Islands. It is also found off Libya, Egypt and Turkey.

The green turtle is concentrated further east, in the Levantine basin. It also appears in the Adriatic Sea and more rarely in the western part of the Mediterranean.

The leatherback turtle is observed in the open sea throughout the basin, with a more marked presence in the Tyrrhenian Sea, the Aegean Sea and around the Strait of Sicily.

Only two species breed in the the Mediterranean

The loggerhead and green turtles are the only turtles to breed in the Mediterranean, mainly in the eastern part. For the loggerhead, the sites are located in Greece, Turkey, Libya, Tunisia, Cyprus and southern Italy.

In recent years, egg-laying has been observed in the west of the basin, along the Spanish coast, in Catalonia, but also in France, in Corsica or in the Var!

In 2006, in Saint-Tropez, the nest of a loggerhead was unfortunately destroyed by heavy rain. In Fréjus in 2016, a few new hatchlings had been able to reach the sea thanks to close monitoring by teams from the French Mediterranean Sea Turtle Network (RTMMF).

In the summer of 2020, two new nests in Fréjus and Saint-Aygulf made the headlines, especially since several dozen baby turtles were born!

What do the scientists say?

From a scientific point of view, it is too early to draw conclusions on the “why” of these clutches.

Are more females nesting in this, the northernmost area for loggerheads to lay their eggs? Is there more compliance pressure from sea users? Is it a combination of several phenomena?

It’s hard to say… It seems quite clear, however, that civil society is becoming more aware of the presence of turtles and – hopefully – more concerned about the future of these fragile heritage animals.

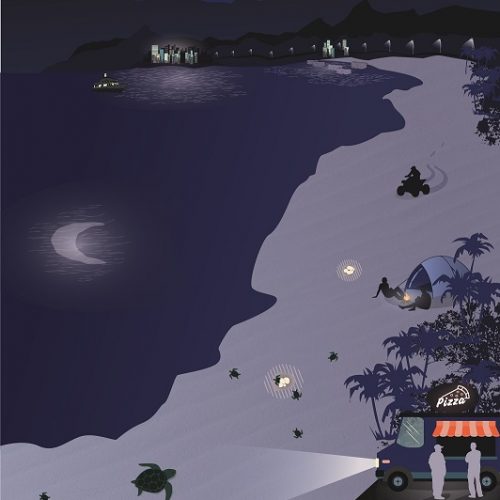

If the turtles come to lay their eggs on our beaches, it is up to us to give them some space, to create less disturbance at night and to adapt the beach lighting which can dissuade the females and disorient the juveniles.

‘Homing’, the innate ability to return home

Genetic analyses prove it: not all loggerheads observed in the Mediterranean are born there!

About half of them would be born in the Atlantic Ocean on the coasts of Florida, Georgia, Virginia or in Cabo Verde. They are born on these remote beaches, enter the Mediterranean via the Strait of Gibraltar to feed, and when they are adults, return to the beach where they were born in the Atlantic to lay their eggs.

The situation for green turtles is different. All those who live in the Mediterranean were born there. Their population is therefore genetically isolated, with no connection to other green turtle populations elsewhere in the world.

Poor genetic mixing for loggerheads

Until the end of the last great ice age, 12,000 years ago, the cold climatic conditions in the Mediterranean did not allow loggerhead turtles to settle or feed, let alone reproduce .

Incubation of eggs is only possible if a temperature of 25°C is maintained for a minimum of 60 days. It was only when temperatures stabilized at levels close to present-day climatology that the Atlantic loggerhead turtles, which had remained in warmer areas during the ice age, were able to colonize the Mediterranean.

Their presence in the Mediterranean is therefore – relatively – recent.

How many turtles in the Mediterranean?

This is a difficult question to answer! There is no technological way to count all the marine turtles present in such a large maritime area, especially as these great migrants are constantly moving from one area to another.

Knowing the abundance of turtles is a priority in scientific research aimed at conserving marine turtles in the Mediterranean. This is one of the many conclusions of the recent IUCN report, which also gives some estimates: there are between 1.2 and 2.4 million loggerhead turtles in the Mediterranean and green turtles are estimated to be between 262,000 and 1,300,000; extremely wide ranges due to the difficulty of conducting censuses.

While counting individuals at sea is illusory, it is possible to monitor the number of females coming to lay eggs, beach by beach, year after year. Nearly 2,000 loggerheads come ashore to lay eggs, mainly in the Levantine basin (Greece, Turkey, Cyprus and Libya).

Good news, the number of clutches is increasing! On about twenty reference sites, the annual average has increased from 3,693 nests per year before 1999 to 4,667 after 2000, an increase of over 26%! The same goes for green turtles. At 7 reference sites in Cyprus and Turkey, the annual average number of nests increased from 683 to 1,005 between before 1999 and after 2000, i.e. + 47%!

These very positive trends show that conservation efforts are paying off and deserve to be continued and expanded.

What does the IUCN say about Mediterranean turtles?

This new report sheds new light on the key nesting, feeding and hibernation sites of Mediterranean turtles.

It also proposes a series of recommendations and actions at the basin level for managers, policy makers and the general public.

This new report sheds new light on the key nesting, feeding and hibernation sites of Mediterranean turtles.

It also proposes a series of recommendations and actions at the basin level for managers, policy makers and the general public.

Priorities include:

- Strengthen monitoring and protection of nesting areas

- Conserve priority feeding and hibernation areas (e.g. through Marine Protected Areas) and preserve seasonal migration corridors

- Reduce by-catches by adapting fishing techniques and training fishermen in the proper way to release caught specimens

- Fight against all forms of pollution

- Strengthen the protection networks by actively involving every actor in society (marine professional, fisherman, conservation expert, researcher, political decision-maker or ordinary citizen)

- Improve the network of rescue and relief centres, which are currently too unevenly distributed and virtually absent from the southern and eastern shores of the Mediterranean.

Some coral species are being studied to better understand calcification or the spread of disease, while others are being studied for their molecules that protect against sunlight or aging. Corals are the basis of many research projects to find tomorrow’s drugs or cosmetics or to understand how certain diseases are formed.

Coral reefs have an important ecological role. Often in waters that are not very rich in phytoplankton, the source of the marine food chain, they offer real oases of life in the middle of the oceanic desert. They also provide an ideal natural barrier against cyclones, storms and erosion as they absorb the power of the waves.

Coral reefs: an oasis of life

Although they cover barely 0. 2% of the ocean’s surface, coral reefs are home to 30% of marine biodiversity! For fish and other marine animals, corals are real shelters against predators, but also a reproduction and nursery area for many species. They are the essential foundation of marine life in the tropics.

Coral reefs provide direct sustenance to 500 million people worldwide through fishing, and reefs protect coastlines more effectively than any man-made structure from swells and tsunamis.

Read more:

- Coral reefs by Jean Jaubert, marine biologist and former director of the Oceanographic Museum

A major asset for tourism

They are a major tourist attraction and generate a significant part of the economic income of the tropical regions where they are found. Annual net profits of several million or even billion euros per year. Australia, Indonesia, the Philippines, more than a hundred countries benefit from this ” reef tourism “.

Medical Perspectives

Humans and corals have a common genetic heritage. Studying coral and the molecules they produce offers many prospects for human and animal health. The genome, the genetic material of the Acropora coral, has 48% correspondence with that of a human being. While the latter shares only 8% of correspondences with Drosophila, a fly used by laboratories as a model for genetic work! This represents incredible prospects for medical research!

Read more:

- Coral reefs by Jean Jaubert, marine biologist and former director of the Oceanographic Museum

- Why don’t corals get sunburned? by John Malcolm Shick, Professor of Zoology and Oceanography

- Why don’t Corals Get sunburned? by John Malcolm Shick, Professor of Zoology and Oceanography

- The Institute’s coral sheets

Back on our shores after 30 years of effort

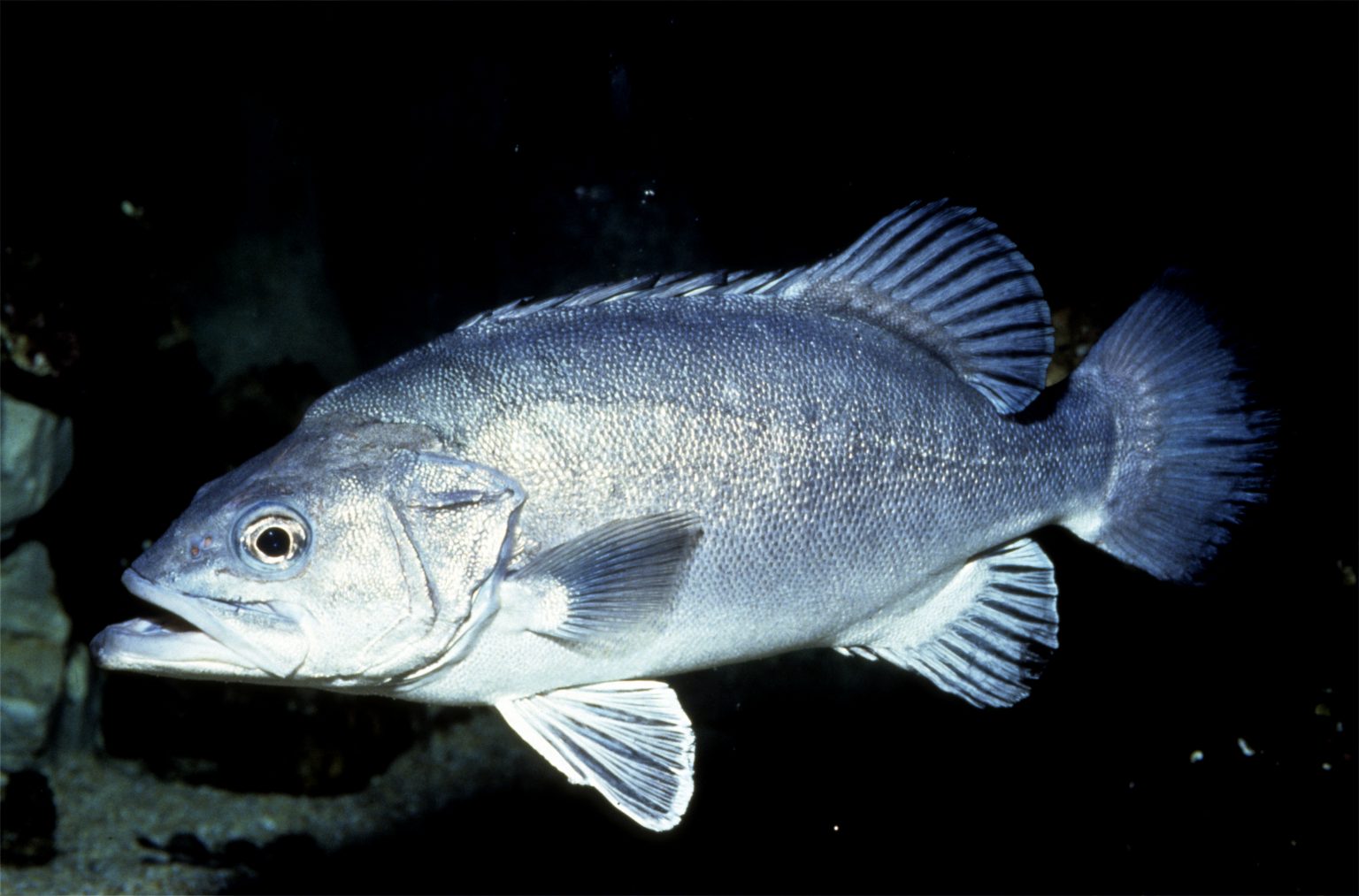

An icon for many scuba divers, both for its size (it is one of the largest bony fish in the Mediterranean) and its rarity, the brown grouper Epinephelus marginatus had almost disappeared after decades of overfishing and poaching. Thanks to strong protection measures, it is making a strong comeback in the waters of the French and Monegasque Mediterranean, especially in protected areas, allowing the underwater hiker to admire its unique and majestic behaviour. Watching it while diving is a privileged and magical moment, a memory that you will keep in your head for a long time! The return of the grouper is not a coincidence but the result of 30 years of efforts, an example that should inspire us to better protect endangered species in the Mediterranean! Explanations…

Male or female? Both of them! A little biology...

The brown grouper lives between the surface and 50 to 200m depth, in the Atlantic Ocean (from the Moroccan coasts to Brittany) as well as in the whole Mediterranean Sea. It is also found off Brazil and South Africa, but researchers wonder if it is a homogeneous population or distinct subpopulations. The mystery remains today!

It likes coastal rocky habitats rich in crevices and cavities. The juveniles, more littoral, are sometimes observed in a few centimeters of water. Its size varies from 80 cm to 1 m or even 1.5 m for the largest individuals.

The grouper changes sex during its life: “protogynous hermaphrodite”, it is first female then becomes male when it reaches 60 to 70 cm, at the age of 10 to 14 years.

Regulator and indicator of the state of the marine environment

A super-predator at the top of the food chain, the grouper hunts its prey (cephalopods, crustaceans, fish) at lower trophic levels, thus playing the role of regulator and contributing to the balance of the ecosystem. It is also an indicator of environmental quality. The abundance of groupers reflects the good condition of the food chain that precedes it, the presence of rich food and the expression of moderate poaching and fishing pressure. Because of its very high commercial value, the brown grouper remains highly sought after by fishermen and underwater hunters throughout its distribution area. Its numbers are in sharp decline and it is classified by the International Union for Conservation of Nature as a vulnerable species.

Did you know?

8 species of groupers are present in the Mediterranean. Among the 6 species observed in Monaco, the brown grouper Epinephelus marginatus is the most frequent, then comes the impressive cernier, still called wreck grouper Polyprion americanus. The canine grouper Epinephelus caninus, the badèche Epinephelus costae, the white grouper Epinephelus aeneus, the royal grouper Mycteroperca rubra are much more discrete.

Grouper protection works!

The rarefaction of this fish has led France and the Principality of Monaco to adopt strong protection measures within the framework of international conventions (Bern, Barcelona). The moratorium set up in continental France and in Corsica since 1993 prohibits underwater hunting and fishing with hooks. Field studies show the effectiveness of these protection measures: young groupers are now present on all the coasts, and in the marine reserves the populations have recovered. But this comeback remains very fragile. The moratorium is to be reviewed every 10 years. The future of the grouper will therefore be decided in 2023. If hunting were to be allowed again, more than 30 years of effort could be wiped out in a few weeks!

In Monaco, the Sovereign Order of 1993, reinforced by theOrder of 2011, prohibits all fishing and ensures the protection of the brown grouper as well as the corb, another vulnerable species. Thanks to this specific protection, to the Larvotto Reserve and to the presence of very favourable habitats and abundant food, the brown grouper is once again abundant in the waters of the Principality of Monaco, particularly at the foot of the Oceanographic Museum.

Did you know?

Why do we still find brown groupers on the fishmongers’ shelves? Simply because the use of nets to catch them is still allowed. Specimens imported from unregulated areas may also be offered for sale. It is up to us as consumers to avoid buying endangered species!

The principality takes care of the groupers

Since 1993, under the control of the Environment Department, the Monegasque Association for the Protection of Nature, assisted by the Grouper Study Group, has been carrying out a regular inventory of groupers in Monegasque waters, from the surface to a depth of 40 m, with the natural participation of divers from the Oceanographic Museum. From year to year, the numbers observed increase (15 individuals in 1993, 12 in 1998, 83 in 2006, 105 in 2009, 75 in 2012). Large specimens of 1.40 m are now numerous and juveniles of all sizes are observed on the shallows.

The Oceanographic Museum also gets wet...

The Museum also comes to the rescue of specimens in difficulty that are entrusted to it by fishermen or divers, as was the case at the end of 2018, with several individuals affected by a viral infection, already observed in the past on several occasions in the Mediterranean in Crete, Libya, Malta, and Corsica. With the Monegasque Marine Species Care Centre created in 2019 to care for turtles and other species, these interventions are now facilitated. The cured groupers return to the sea to be in protected areas such as the Larvotto Underwater Reserve. Watch the video of the release of the young grouper “Enzo”.

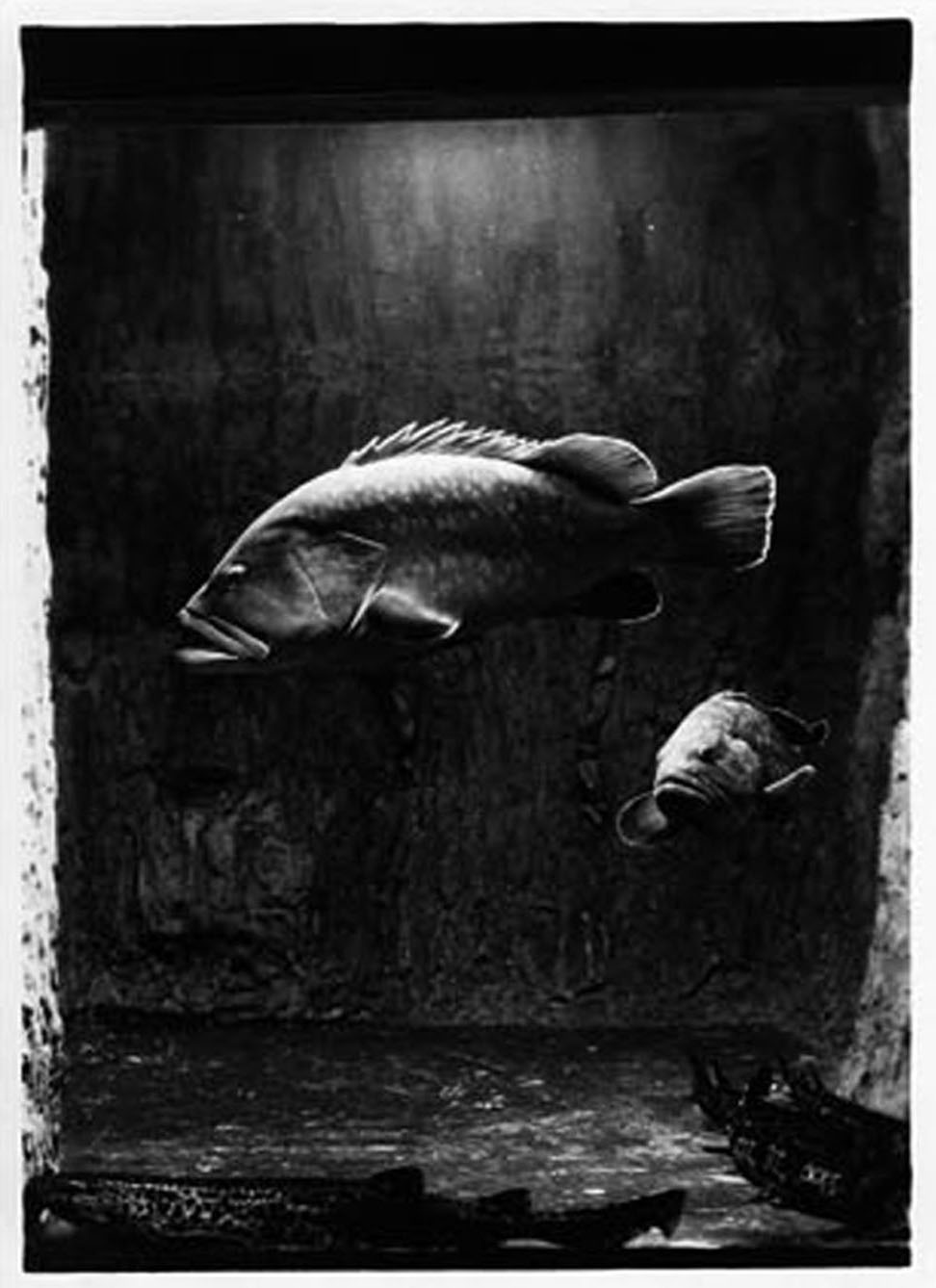

The merou, a long-time star at the aquarium

Many visitors discover this heritage species at the Oceanographic Museum. This is not new, since the Aquarium, then directed by Doctor Miroslav Oxner, was already presenting them in 1920! One of them, now kept in the Museum’s collections, lived there for more than 29 years. Four different species (badèche, brown, white and royal grouper) can now be seen in the completely renovated section dedicated to the Mediterranean.

If the grouper intrigues visitors, it also inspires artists! Numerous objects bearing his likeness, both works of art and manufactured objects, can be found in the collections of the Oceanographic Institute!

In 2010, a grouper from the Museum was used as a model for the 100 Reais banknote issued by the Central Bank of Brazil, which is still in circulation today, and the Principality even dedicated a postage stamp to it in 2018!

An asset for the blue economy, tourism and fishing...

Tourists come from far and wide to observe the underwater fauna and a “successful” dive is often one during which the brown grouper has been observed! Several studies show that a live grouper brings in infinitely more money during its existence than if it is caught to be consumed!

Brown grouper particularly thrive in effectively managed marine protected areas (MPAs), which provide important biodiversity conservation and economic development benefits. By protecting and restoring critical habitats (migration routes, predator refuges, spawning grounds, nursery areas), MPAs contribute to the survival of sensitive species such as brown grouper. Adults and larvae of different species living within an MPA can also leave and colonise other areas, a process known as spillover. When eggs and larvae produced within the MPA drift outside, this is called Dispersal. Species with a high market value (brown grouper, lobster, red coral) travel considerable distances, providing ecological and economic benefits in remote areas! Adult brown groupers stray one kilometre outside the MPA boundary. As for the larvae, they travel several hundred killometers!

The answer is yes! There are several thousand whales living in the waters of the Mediterranean. It is even not uncommon to see their breath from far away, on crossings to Corsica, for example. But beware: human activities are a source of disturbance for these giant mammals. It is therefore very important to do everything possible to preserve their peace of mind.

There are nearly twenty species of marine mammals in the Mediterranean, eight of which are considered common: sperm whales and fin whales, of course, but also dolphins (common, blue and white, Risso’s, bottlenose dolphin), pilot whales and ziphiuses. Other species are observed on a very occasional basis such as the minke whale, the killer whale, the humpback whale and very recently a young grey whale!

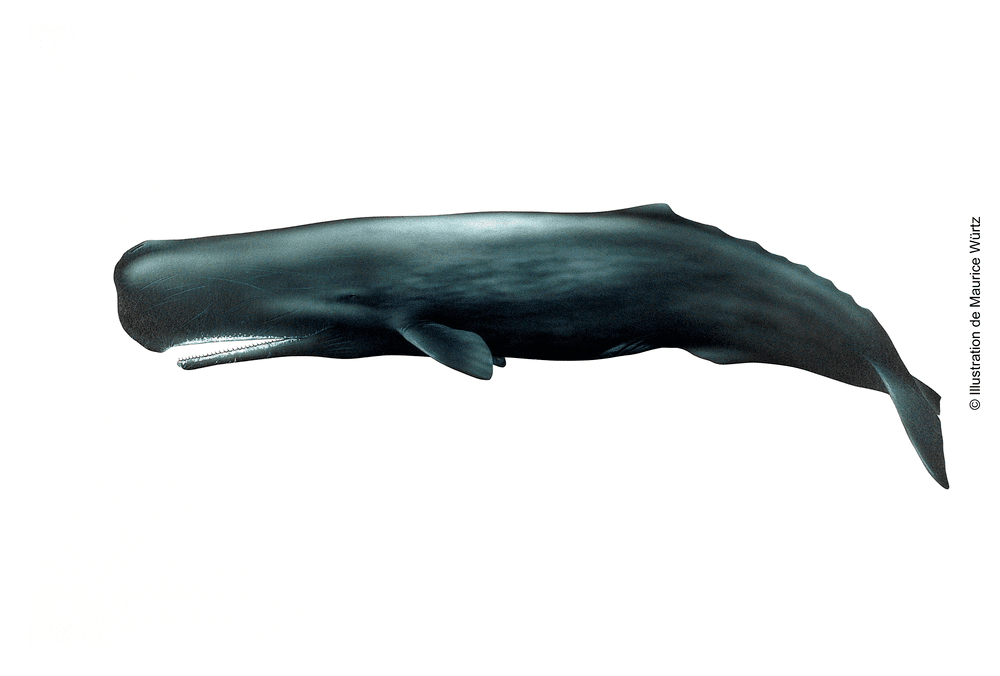

Sperm whale Physeter catodon

Baleen or teeth?

In common parlance, we tend to refer to all large cetaceans as “whales”. However, only “baleen whales” (mysticetes) are really whales.

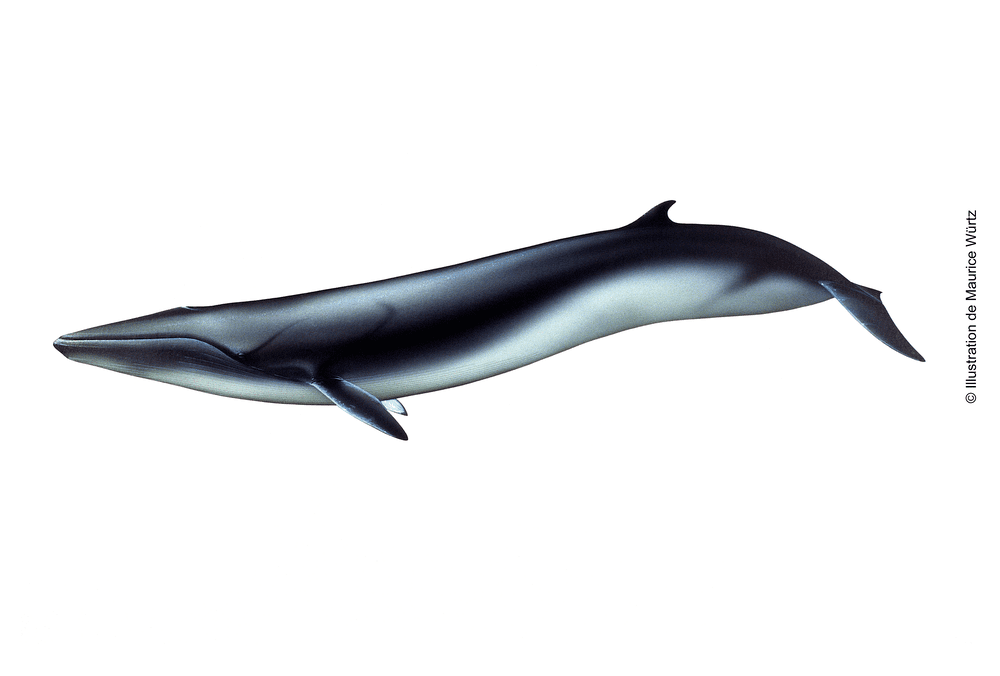

The fin whale (up to 22 metres and 70 tonnes) is the main baleen whale in the Mediterranean.

It rubs shoulders with numerous “toothed cetaceans” (odontocetes), the largest of which is the sperm whale (up to 18 metres and 40 tonnes).

Despite its imposing stature, this whale is not strictly speaking a whale, and belongs to the same group as orcas, dolphins or pilot whales.

A giant of the seas

The fin whale is the second largest mammal in the world, just behind the blue whale!

Although it is still difficult to assess the exact size of its population (as individuals are constantly on the move and dive regularly), it is estimated that about a thousand individuals live in the protected area of the Pelagos Sanctuary, which aims to protect marine mammals in the western Mediterranean over a vast territory including French, Italian and Monegasque waters.

The fin whale feeds mainly on krill, small shrimp that it traps in its baleen plates in large quantities.

Fin whale Balaenoptera physalus

Risk of collision

Fin whales can live up to 80 years, if their trajectory does not meet that of the fast ships that are common in summer, which they find difficult to avoid when breathing on the surface.

As for sperm whales, collisions are a real danger and a proven risk of mortality. Hence the interest in developing techniques in partnership with shipping companies to inform ships of the presence of cetaceans in real time, to equip ships with detectors and thus prevent collisions with these large mammals.

Discover the different species of marine mammals in the Pelagos Sanctuary.

Fin whale Balaenoptera physalus

Saving coral reefs: many solutions

To try to save coral reefs, we must act urgently and simultaneously against global and local threats, reduce pollution, protect areas that are still in good condition, restore degraded areas, and develop a blue economy around certain reefs, which protects and enhances them. But first and foremost, we must fight against climate change!

Fighting global warming

This is the first emergency to slow down ocean warming and limit coral bleaching episodes. To achieve this, we must drastically reduce greenhouse gas emissions in order to stay below 1.5° C of warming, save energy, gradually but resolutely move towards a low-carbon economy, and use more renewable energy. Less CO2 in the atmosphere also means that the ocean acidifies less quickly and has less impact on organisms that, like corals, create a calcareous skeleton.

Fighting against pollution

Pollution suffocates or poisons the reefs. All forms of chemical and physical pollutants that end up in the sea must be eliminated! It is up to all of us to adopt the right practices, the right gestures, everywhere and in all circumstances, including inland. Together, let’s reduce, reuse and recycle to limit the consumption of resources and the creation of waste.

For more information:

We can all take action! Discover 10 things you can do on holiday or in your daily life to preserve coral reefs.

Promoting the blue economy

Developing sustainable economic activities that respect coral reefs and create value and jobs in many economic sectors (tourism, fishing, aquaculture, agriculture, maritime transport) is possible! Among the main actions to be carried out: stopping the concreting of the coastline, limiting urban sprawl and infrastructure construction (industrial, tourist), particularly in fragile areas. For responsible tourism, we must develop scuba diving that respects species and ecosystems, limit the number of divers if necessary, provide better supervision and raise awareness, and use anchor buoys. For a sustainable agriculture, the priority is to protect waterways (because everything reaches the sea), stop deforestation and limit pesticides.

For responsible fishing and aquaculture, there is an urgent need for better control of practices and to fight against all forms of illegal fishing.

Protecting coral reefs and associated ecosystems

Coral reefs will have a better chance of being preserved if representative (in good condition and rich in species), networked, effectively managed marine protected areas (MPAs) are created where human activities are regulated.

Scientists recommend protecting the so-called “refuge” zones, particularly those in the “mesophotic” zone, located between 30 and 150 m deep and therefore relatively sheltered from marine heat waves. The corals found there are less vulnerable to bleaching and thus likely to serve as a reservoir to promote the recolonisation of degraded areas. At the same time, seagrass beds and mangroves must also be protected. These coral reef-related ecosystems play a major role in carbon cycling and storage, helping to combat the accumulation of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.

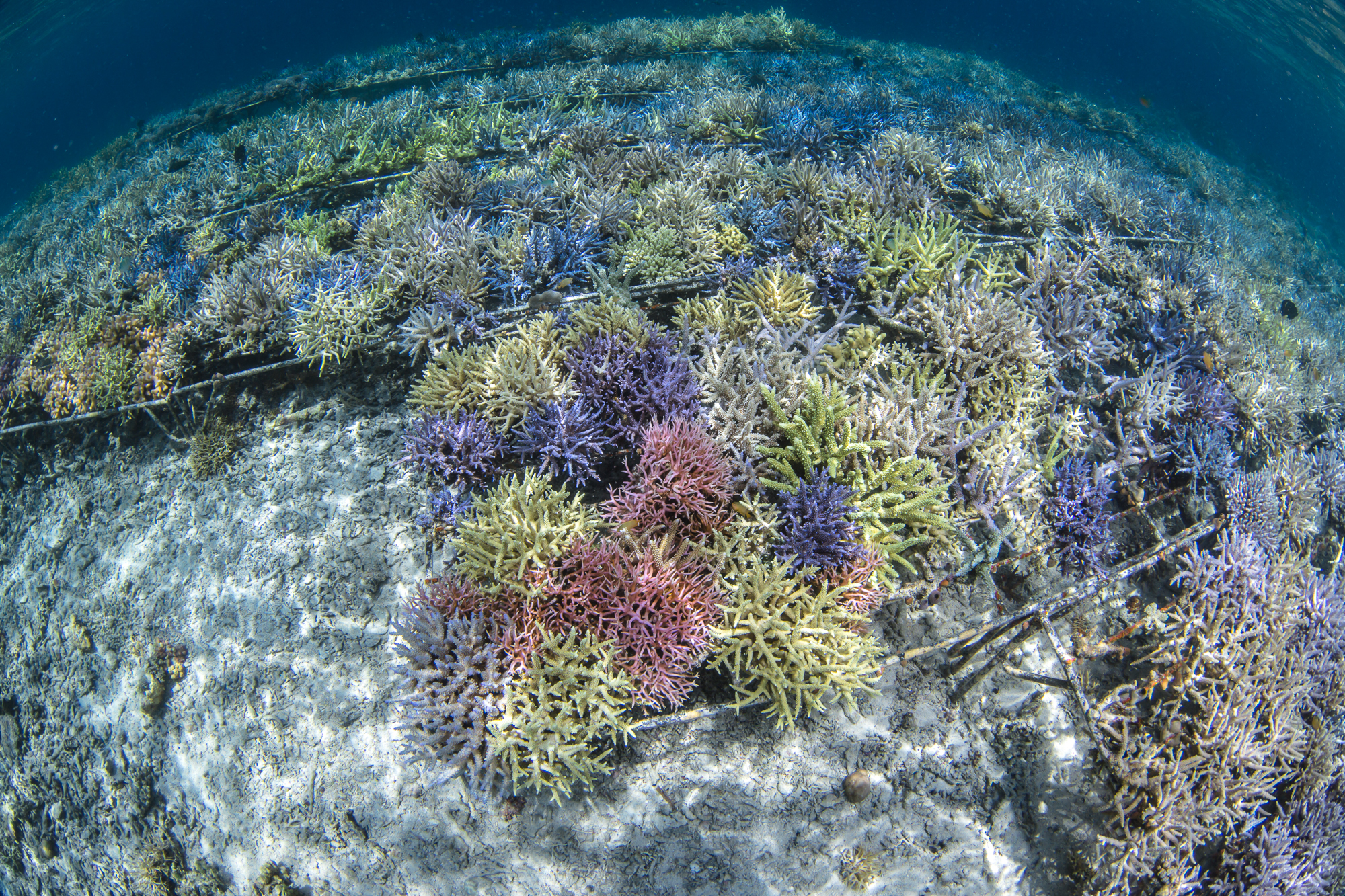

Restore degraded reefs

Wherever possible, we must try to restore reefs degraded by human activities. This can be done by transplanting coral from one site to another(ex-situ), or by cultivating it in situ(in situ), where a fragment of coral can reform a new colony. Engaging local communities in this process and eliminating the local factors that had caused the loss of corals are two prerequisites for the success of such operations. Researchers are now developing new methods based on assisted evolution, selecting species or strains of corals that are resistant to heat waves, and re-implanting them to reform various reefs. They also try to collect gametes, eggs, larvae of corals, and to spread them on the reef, for example with aerial means. Seagrass beds and mangroves can also be restored by replanting or cultivating them, using methods based on scientific recommendations.

Creating a Global Coral Conservatory

Create a coral “bank”, just as there are seed banks. The one initiated by the Scientific Centre and the Oceanographic Museum will constitute a Noah’s Ark of 1000 species distributed in the largest aquariums and research centres in the world, with the aim of preserving the strains and re-implanting them in devastated areas. It will also make it possible to study the resistance of species to heat and to select the strongest varieties, an important contribution to their preservation, if we also manage to limit global warming.

Read more:

Corals host microalgae, called zooxanthellae, in their tissues. They are the ones that give the corals their colors. Depending on the pigments they contain, corals abhor pretty hues ranging from orange brown to purple.

These algae live in symbiosis with the coral, which means that everyone benefits.

Coral is carnivorous and feeds on small animals that pass by but this does not provide it with enough energy to grow and reproduce. About 75% to 90% of the coral’s needs are supplied by algae. Through the process of photosynthesis and in the presence of light, algae transform mineral salts (nitrogen and phosphorus) into organic matter, while consuming carbon dioxide and releasing oxygen. The coral brings the carbon dioxide it rejects by consuming oxygen during its respiration.

When the algae leave, the coral turns white.

Why do corals bleach?

When the algae are stressed, they are expelled by the coral and it is then that their transparent tissues reveal the white skeleton. This stress is caused either by bacteria or viruses (the corals are then sick) or by pollutants, or by the rise in temperature of the sea water.

It is this last point that worries climate specialists. According to the special report “The Ocean and Cryosphere in the Face of Climate Change” published by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in September 2019, the ocean has absorbed more than 90% of the heat accumulated in the atmosphere by the greenhouse effect since the industrial revolution!

Marine heat waves (comparable to our terrestrial heat waves) are likely to become 20 times more frequent even if the increase in atmospheric temperature is maintained at 2°C.

These heat waves are harmful to coral reefs, 90% of which are likely to disappear.

Read more:

Corals belong to the large family of Cnidaria, which includes marine invertebrates that have stinging cells such as jellyfish, gorgonians and sea anemones.

Corals do not only live in tropical seas. Under the name coral, we find different species, some of which live in the Mediterranean. In particular the famous red coral, the one whose skeleton is used to make magnificent jewellery.

Corals live alone or in colonies. A distinction is made between hard corals (Scleractinians), which include reef-building corals, and soft corals, which do not have a skeleton. Both categories are found in the Mediterranean.

The red coral

The red coral (Corallium rubrum) is recognizable by the bright red colour of its skeleton contrasting with its small white polyps that tirelessly shake their tentacles.

It is found specifically in the Mediterranean Sea and the western Atlantic (from the south of Portugal to Cape Verde) where it generally lives attached to the ceiling of caves or on drop-offs. It grows very slowly, a few millimetres per year.

It is its vivid colour, which keeps its brilliance even out of water, which made its reputation and earned it its use in the making of jewellery or objects.

Widely fished, with destructive methods it almost disappeared. Its fishing is now regulated and closely monitored, but it is still highly coveted by fishermen.

Coralligenous drop-offs

These large structures are found between 30 and 100 meters underwater. Fixed species such as gorgonians, sponges or black corals capture particles and micro-organisms in the currents to feed. These animals, which have calcareous, siliceous or horny skeletons, participate in the construction and consolidation of the drop-off.

Solitary corals in the Mediterranean

There are several species of solitary corals in the Mediterranean with particularly evocative names such as the yellow coral with the pretty name of buttercup, pigs’ teeth (Balanophyllia species) or dogs’ teeth (Caryophyllia species). They live attached to rocks from the surface to nearly 1000 meters for some species. From a few centimetres in diameter to 2 to 4 centimetres high, some like the Pigtooth have their tentacles rather short, while the Dogtooth corals are recognizable by their long and numerous tentacles ending with a small button that inflates and deflates.

Reef-building corals

In the Mediterranean, there are hard corals similar to the builders of tropical reefs: the cladocores which can be found in the form of “potatoes” that can reach a diameter of some 50 centimetres. Their shape depends a lot on the depth at which they are found, the light and the currents.

Soft corals

There are also soft corals (without a calcareous skeleton) that can be mistaken for sea animals. Some are colonial and form carpets on the rocks while others are solitary.

Read more:

- Thematic sheet: Scleractinian corals of the Mediterranean by Christine Ferrier Pagès

- Marine species reference: DORIS site

- Institute’s coral sheets