Like all animals, coral reproduces sexually (by releasing sperm and eggs) but also asexually (by taking cuttings like a plant)! Let’s discover the mysterious reproduction of corals.

Sexual reproduction

Like all animals, corals reproduce sexually. There are male polyps that produce male gametes (sperm) and female polyps that produce female gametes (eggs). Corals that live in a colony can have both males and females in the same colony, so the coral is said to be hermaphrodite.

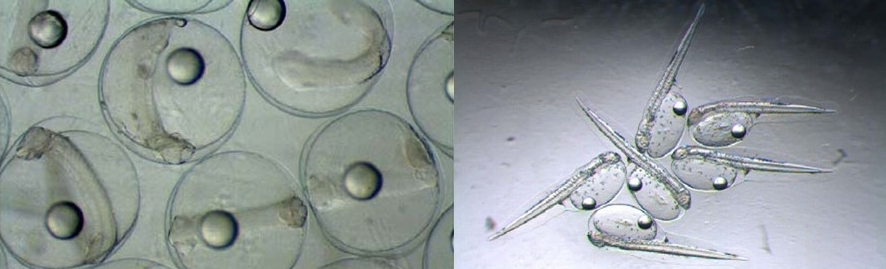

The fertilization that takes place during the meeting between the male and female reproductive cell can be of two natures: the fertilization is external, and the spermatozoids go to the meeting of the ovules in full water, after being ejected by the polyps. Fertilization is internal, the male polyps emit spermatozoa which are received in a female polyp incubator.

During fertilization, an egg cell is formed which gives birth to a ” planula larva ” that wanders for some time in the ocean currents before dropping to the bottom. The larva then transforms into a polyp which is fixed on a rock and becomes a new colony. Sexual reproduction allows the propagation of corals in new spaces while ensuring a genetic mixing.

Asexual reproduction

The coral, like other animals, has the particularity of being able to reproduce in an asexual way, i.e. without releasing sexual cells. Coral fragments, either because of natural disturbances (storm, cyclone or predator) or because of voluntary or involuntary human action. If the fragmented piece, which can be called a cutting, is in a favourable environment, it will continue to grow and form a new colony and thus strengthen the cover locally on the sea floor. It is this particularity that offers the possibility to aquariums to populate their tanks without taking species from the natural environment.

Various institutions involved in the knowledge and protection of the oceans (Oceanographic Institute, Scientific Centre of Monaco, Prince Albert II Foundation, Explorations de Monaco) have combined forces to raise public awareness and act in favour of the survival of coral reefs. High-level scientific research, organization of symposiums, political influence, mobilization of the media, financing of NGO projects… The actions are numerous.

A commitment initiated by Prince Albert I

The Oceanographic Museum of Monaco, created by Prince Albert I of Monaco (1848-1922) with the aim of “knowing, loving and protecting the oceans”, houses one of the oldest aquariums in the world. It was at the end of the 1980s that the aquarium’s teams, accompanied by Professor Jean Jaubert, perfected the maintenance and reproduction of corals outside their natural environment.

Monaco at the initiative of the World Coral Conservatory

What if the major crisis of biodiversity loss and global warming that we are currently experiencing caused corals to disappear? In response to this threat, the Scientific Centre of Monaco and the Oceanographic Museum have decided to create a World Coral Conservatory in order to preserve the strains of many species of coral in aquariums so that they can be studied before eventually attempting to re-implant them in suitable areas.

Currently, all the aquariums in the world cultivate nearly 200 species of corals. The objective is to protect 1000 species of corals within 5 years, i.e. two thirds of the existing species. These naturally occurring corals will be distributed to the world’s largest aquariums and research centres. The Oceanographic Museum of Monaco is coordinating this beautiful project with the Scientific Centre of Monaco.

Read more:

An activity that creates controversy

Unlike many marine species (salmon, sea bass, sea bream), the aquaculture of large tunas is not perfectly mastered and continues to be the subject of extensive experimentation in several countries (Australia, Japan, Europe) in order to carry out the complete cycle of farming over several generations, with a view to eliminating catches at sea and maximising profits. Proponents of large tuna aquaculture believe that farming will reduce pressure on wild stocks. Environmental organizations believe that the problem will just be displaced, with fishing pressure shifting to the “forage fish” at the base of the food chain, potentially disrupting the entire marine ecosystem.

Tuna fattening

Bluefin tuna farming is based almost exclusively on “fattening”, a technique that consists of catching young tuna in the wild and growing them in large fish farms to commercial size. Fed with “feed” fish (10 kg of sardines or mackerel will produce 1 kg of tuna), the fish quickly fatten up before being slaughtered and exported to consumer countries, mainly Japan, far from where they are produced, contributing to the emission of greenhouse gases.

The activity is controversial; for sustainable fishing advocates, it decimates future breeders and lacks transparency.

As practiced today, bluefin tuna aquaculture appears to be far from sustainable as it raises, among other issues, the problem of marine resource management, ecological impacts and greenhouse gas emissions.

Experts' Corner

Three species with high market value are fattened at the fattening sites: Atlantic bluefin tuna(Thunnus thynnus), Pacific bluefin tuna(Thunnus orientalis) and southern bluefin tuna(Thunnus maccoyii). More than 50 farms, located in Australia, Mexico, Japan and the Mediterranean produced a total of 36,350 tons in 2014, including 14,500 tons of Atlantic bluefin tuna, mainly in Italy, Spain, Croatia, Malta, and Turkey.

The vast majority of bluefin tuna caught in the Mediterranean by industrial fisheries is destined for the fattening activity that serves the Japanese market.

Prudence and discernment

A few years ago, with stocks on the verge of collapse, bluefin tuna consumption was widely discouraged, leading the Principality of Monaco to adopt a consensus moratorium on its consumption. With stocks now in better shape, it is possible to eat bluefin tuna, but with great care. Ethic Ocean suggests to limit the quantity consumed, to privilege the “East Atlantic and Mediterranean” origin and to choose the specimens fished with the rod, of more than 30 kg (thus with sexual maturity). On the other hand, the consumption of bluefin tuna from the “Western Atlantic” stock and other overexploited tuna species, Pacific bluefin tuna (Thunnus orientalis) and Southern bluefin tuna (Thunnus maccoyii) when they come from the southern part of the three oceans, should be avoided.

What criteria should be applied?

For Mr.GoodfishUnder the Prince Albert II Foundation’s sustainable consumption programme, bluefin tuna can be eaten but only if it is wild, comes from certain fishing areas (mainly the Atlantic) and is caught outside its breeding period at a recommended minimum size of 120 cm.

The labels

Some labels offer bluefin tuna fished in a responsible manner in accordance with the regulations in force and the specifications specific to the fishing method (longline, pole and line). It concerns bluefin tuna fished by line and includes the right actions to take when catching “by-catch” species (sharks, pelagic rays, sea turtles, birds).

Our best advice: when buying tuna or other seafood, be curious and demanding! Do not hesitate to ask questions to the salesman or the restaurant owner, they are there for that! Try to identify the species you are consuming, where it was caught or produced, the method used and how it was sustainably caught or farmed. Never buy bluefin tuna from recreational or sport fishing, it is forbidden!

12 AUGUST 2020: More on Atlantic bluefin tuna certification...

The Marine Stewardship Council has just awarded the ” sustainable fishing label ” to a fishery using longlines (large lines with hooks) in the eastern Atlantic Ocean (55 tons caught in 2018). This decision comes after an independent legal expert found that the company’s measures fully met the criteria for sustainable fishing. Other fisheries are reportedly in the process of applying for certification.

As a precautionary measure, in view of the scientific uncertainties about the state of the stock, some NGOs are currently opposed to any certification of Atlantic bluefin tuna. For WWF, ” the MSC certification of bluefin tuna is an alarming signal that the outcome is driven by industry demand rather than scientific evidence of sustainability… This may be a dangerous trend that may threaten the full recovery of bluefin tuna and our ability to restore the health of the world’s oceans by 2030. »

In the 2015 European Red List of Marine Fishes compiled by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), Atlantic bluefin tuna is listed as Near Threatened.

Overfishing and overcapacity of fishing fleets are the main cause of the depletion of bluefin tuna.

Did you know?

The scourge of plastic at sea also threatens bluefin tuna. According to a 2015 study of large predators in the Mediterranean (tuna and swordfish), 32.4% of bluefin tuna specimens surveyed contained plastic in their stomachs, a real concern for the IUCN and a wake-up call about the potential effects of this debris on human health.

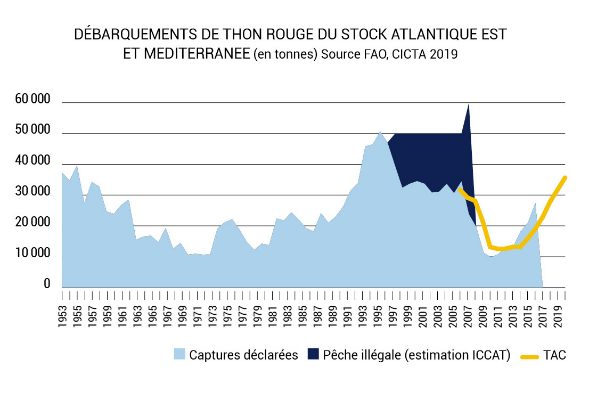

In 2006, in order to avoid a total collapse of the populations, a recovery plan for theEastern Atlantic and Mediterranean was adopted, including measures to monitor and control fishing activities (closed seasons, obligation of a “minimum conservation size” of 115 cm or 30 kg (certain types of fishing have derogations at 8 kg or 75 cm), ban on reconnaissance aircraft, presence of observers on board vessels, traceability of catches, etc.), but the fishing quotas are still too high

A small victory at CITES

Under pressure from NGOs and certain states (including the Principality of Monaco and France) who advocate the inclusion of the species in Annex 1 of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) – which would have the effect of prohibiting international trade – the quota was revised downwards (13,500 tonnes) for 2010, following scientific advice for the first time; an important victory for organisations working for sustainable bluefin tuna fishing!

An improving situation since 2019

Thanks to the strengthening of the recovery plan and more effective control, the bluefin tuna situation is improving from 2009 onwards. Declared catches are decreasing, aerial monitoring shows that young bluefin tuna are more abundant, the spawning biomass is increasing, and fishermen are observing them more regularly. Today, the species is no longer “overexploited” but the current stock, although in better condition, is far from having recovered its preindustrial level, and bad practices such as illegal fishing persist.

With fishing quotas set to increase (32,240 tonnes for 2019, 36,000 tonnes for 2020 – including 19,460 tonnes for the European Union and 6,026 tonnes for France) – the highest levels since the recovery plan was put in place – it will be up to the international community, scientists and consumers to carefully monitor the situation of Atlantic bluefin tuna over the coming years. To be continued, then!

Experts' Corner

Bluefin tuna is one of the most commercially valuable fish species. The management of bluefin tuna fisheries has long been a symbol of the international community’s difficulty in sustainably managing this rare and fragile resource.

Industry professionals and conservation groups are trying to organize themselves to preserve stocks.

Refusing a programmed disappearance

The International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT), created in 1969, succeeded in establishing the first fishing quotas in 1998. In spite of this, in the 2000s, the surge in overfishing led to fears that the species would simply disappear. A strong international mobilization was then born, relayed by Prince Albert II of Monaco and his Foundation.

In partnership with the WWF, the Prince Albert II Foundation is thus among the first organisations to bring the alarming state of bluefin tuna stocks in the Mediterranean to the forefront of the international stage.

With the MC2D association, she convinced the Principality’s restaurant owners and shopkeepers to stop selling this fish, which is on the verge of extinction.

Together with the Oceanographic Institute, it contributes to informing and mobilizing the general public.

Powerful lobbying

In 2010, at the Doha Conference, the Monegasque Government officially requested the listing of bluefin tuna in Appendix I of CITES. This proposal aims to prohibit international trade in the species and to consolidate existing sustainable traditional fisheries. However, CITES finally voted against this proposal, under pressure from Japan.

Representing 80% of the world’s bluefin tuna consumption, Japan is indeed a powerful lobbyist. The debates and international media coverage of this vote have nevertheless reinforced the awareness of all actors in the sector.

They have promoted the establishment of effective management of bluefin tuna fisheries. ICCAT is lowering fishing quotas from 28,500 to 12,900 tonnes per year, in line with the recommendations of scientists and conservationists. Quotas are also more closely monitored by the countries concerned.

Is hope returning to bluefin tuna stocks?

Thanks to this surge and several favourable years, the first hopes of stabilization and recovery of the Mediterranean bluefin tuna population appear from 2012. At its November 2012 meeting, ICCAT decided to follow the scientific recommendations and maintain quotas at their level, in order to confirm and consolidate these first encouraging signs.

Indeed, these recovery indices should be treated with caution because, as the 2012 ICCAT report points out, “although the situation has improved […], there are still uncertainties surrounding the magnitude and speed of the increase in spawning stock biomass”.

Caution is the order of the day

These uncertainties are linked, on the one hand, to the underestimation of illegal fishing, since ICCAT acknowledges that bluefin tuna catches have been “seriously under-reported” for at least the last 15 years; on the other hand, the lack of knowledge of bluefin tuna migratory patterns does not allow for a good assessment of the stocks.

Improving the traceability of bluefin tuna catches in the coming years therefore remains a major challenge. Since 2008, WWF, supported by the Prince Albert II of Monaco Foundation, has been working to advance knowledge on illegal fishing and stock assessment.

For example, WWF encouraged ICCAT to implement an electronic bluefin tuna catch document in 2013 to facilitate the traceability of catches.

How to protect sharks, treated as by-catch?

However, the scope of ICCAT’s work remains limited. Some protection measures also cover swordfish, but sharks remain exclusively treated as by-catch in tuna fisheries. Various species of sharks are endangered by fishing, especially in the Mediterranean. This situation was recognized in the spring of 2013 by CITES. By including five new shark species in its Appendix II, CITES makes international trade in these species subject to guarantees of sustainability of the stocks fished. However, sharks are beginning to be taken into account. Some management measures are applied in Atlantic waters, notably for porbeagle sharks and some particularly vulnerable species. Norway proposed to consider adding sharks to the list of species managed by ICCAT. However, this will require the common will of all member countries, which remains unlikely.

Bluefin tuna, future symbol of good collective management?

A fragile species, bluefin tuna could be transformed from a symbol of resource plundering to one of good collective and shared management based on sound science.

A good dynamic has been initiated in recent years when the situation was critical. However, it will have to be confirmed both by the development of quotas to promote stock recovery and by ICCAT’s ability to extend its action to other threatened species.

The challenge of this rather expensive management model is to consolidate and apply it to other species of lesser commercial value. Indeed, stocks of other large predators are also declining.

How to respond to the

request?

In addition to stock management and catch traceability, which are major issues for ICCAT, other initiatives for the future of bluefin tuna deserve to be highlighted.

The communication campaign “bluefin tuna, a story for the future” and the label “bluefin tuna, artisanal fishing” were launched in 2012 and supported by the French Ministry of the Environment.

They highlight the return of bluefin tuna to the market as a “sustainable” fish when it is fished in a sustainable manner. In addition, some European and Japanese scientific projects for “sustainable aquaculture” aim at the “domestication” of bluefin tuna: .

The reproduction and complete growth of this species in captivity would have the advantage of avoiding the removal of young wild bluefin tuna as has long been the practice for fattening.

The limits of aquaculture

However, bluefin tuna aquaculture, which has been practiced for over 30 years in Japan (Kinki University), is not profitable. Not very popular with Japanese consumers, its products are often destined for export to Taiwan or the United States.

In any case, there is also the question of raising large predators which themselves need a lot of fish to thrive. Farmed salmon already need 4 kg of “feed fish” to grow 1 kg themselves. The bluefin tuna consumes 11 kg of fish to gain 1 kg! An unsustainable model, whose limits we can measure by drawing a parallel with the fact of breeding tigers or wolves for our consumption: this sums up well the way in which man’s taste for marine animals has developed while he thought marine resources were infinite.

Today, it would be more economically and ecologically interesting to let the wild stock recover and to develop a rigorous sustainable fishery.

Reasons for hope

In conclusion, the latest observations on the evolution of the bluefin tuna population seem encouraging. However, it will be necessary to be patient to confirm the effective recovery of the stocks, which is expected around 2022. A new assessment of the Mediterranean bluefin tuna population will be carried out in 2014. It will allow monitoring of actual progress and inform decisions on quotas in the coming years.

In the meantime, caution remains the order of the day and many efforts must be made to improve the quality and reliability of data, to combat illegal fishing, to take account of by-catch and traceability and, above all, to support the development of sustainable small-scale fishing.

Highly effective capture techniques

Bluefin tuna are caught by trawl, hook (handline, troll, longline) or in “traps” (fixed traps near the coast) but they are mostly caught by tuna seiners. In the Mediterranean, more than 90% of bluefin tuna catches are made using this method. These hypersophisticated, powerful and fast industrial fishing vessels (speeding at 16 knots or 50 km/h) are capable of detecting shoals thanks to state-of-the-art electronics (radar, sonar). They deploy the “seine”, a gigantic net dropped in an arc that can cover up to 20 hectares at sea, and catch the quota allocated to them in just a few days.

This method raises questions because it targets large individuals that come to breed in specific areas (especially around the Balearic Islands, Sicily and Malta) over short periods (mid-May to mid-July). Not only does it literally “empty” the marine environment, but it also harms non-targeted and highly endangered species (manta rays, turtles, sharks, cetaceans), especially since many tuna vessels use Fish Aggregating Devices (FADs), intelligent floating systems that attract fish and remotely inform vessels of the quantity of fish present. In this case, by-catches may represent 5% of the fishery.

A fishery considered unfair

In the Mediterranean, many consider industrial seine fishing to be unfair, with a few large vessels sharing out almost all the quota to the detriment of small vessels which are now demanding greater access to the resource.

Bluefin tuna is also the subject of a recreational or sport fishing (when affiliated to a federation), extremely regulated with a ban on selling fishing products. For the year 2020, the quota allocated to recreational fishing in France is 60 tonnes. In Monaco, the catch conditions for bluefin tuna are set by sovereign ordinance.

A traditional fishing scene immortalized by Rossellini

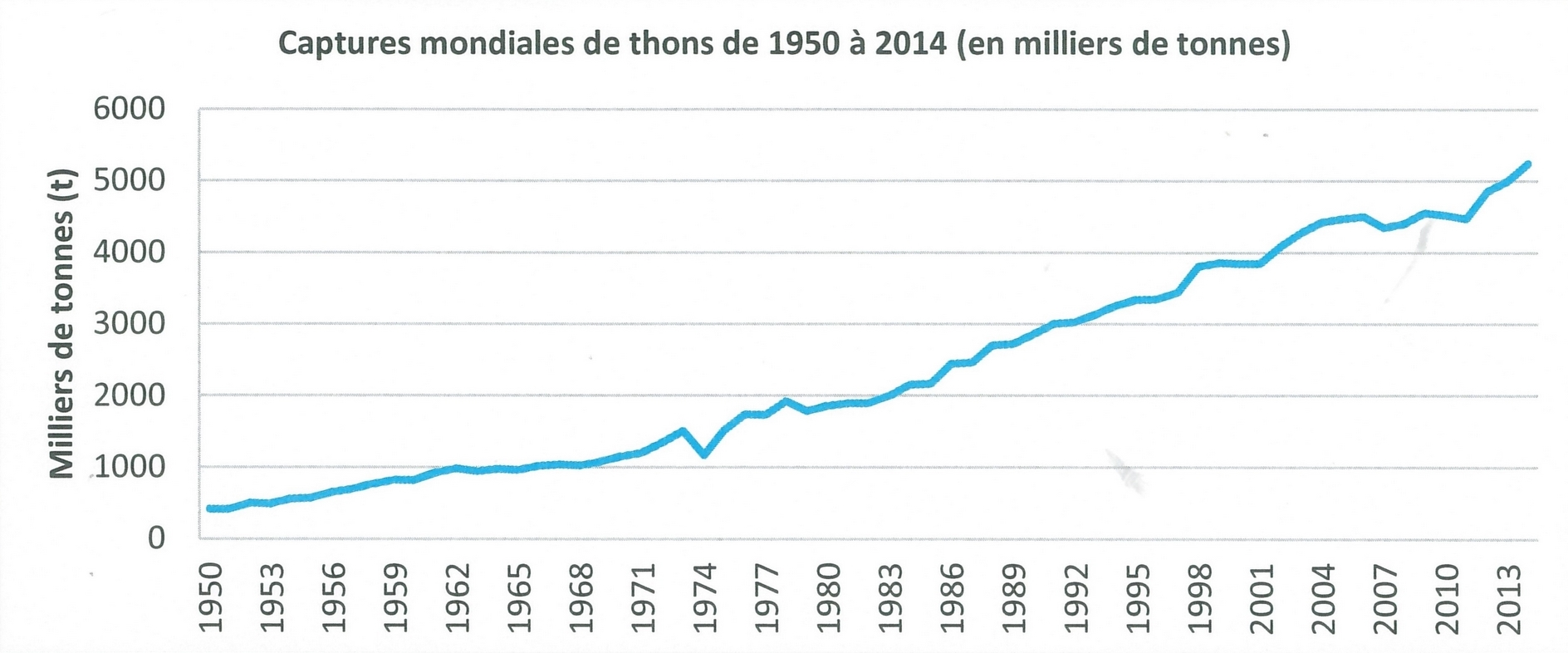

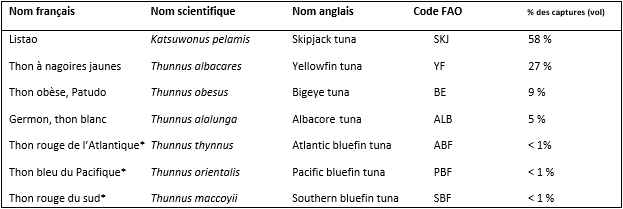

The name “tuna” covers 14 species belonging to 4 different genera(Auxis, Katsuwonus, Euthynnus, Thunnus), which are found in almost all the seas of the world. This large family of fish is of major economic importance in a fully globalised economy.

A growing global catch

In 65 years, the world’s tuna catch has increased by 1, %, from 500,000 to 5 million tonnes, and demand could reach nearly 8 million tonnes by 2025! In terms of export value of seafood products, tuna is in4th place, behind shrimp, salmon and white fish.

At the end of the chain, the value at sale is estimated at 33 billion dollars (i.e. 24% of the world seafood industry). The average per capita consumption of tuna in 2007 (worldwide) is about 0.45 kg per year. In the European Union, more than 2 kg of canned tuna per capita was consumed in 2012!

Experts' Corner

Of the 14 tuna species, 7 are of major commercial importance.

3 species* (Atlantic bluefin tuna, Pacific bluefin tuna, Southern bluefin tuna) represent only 1% of the volume of catches.

Read more:

- Find tuna trade data in the IDDRI report “Tuna: fish and fisheries, markets and sustainability – 2017”

- The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture

FAO – 2020 Edition

In the Mediterranean basin, the Atlantic bluefin tuna has been exploited since the Neolithic period, as attested by the rock engravings in the caves of Levanzo Island, near Sicily (photo below, far right: it is a tuna and not a dolphin!).

It is also present on this Greco-Hispano-Carthaginian bronze coin (200 to 100 B.C.), originating from Gades or Carthago Nova, a Greek city in Spain. Coll. Oceanographic Institute.

A star of Japanese cuisine

Today, bluefin tuna is used to make sashimi and sushi for health-conscious Japanese consumers. Other tunas (skipjack, albacore, yellowfin) are used more in canned and other prepared and preserved products.

Premium bluefin tuna are reaching record prices. In January 2019, at the Tokyo New Year’s auction, a 278kg Pacific bluefin tuna (Thunnus orientalis cousin of the Atlantic bluefin tuna Thunnus thynnus), caught in northern Japan, was auctioned for an incredible 2.7 million euros!

Mediterranean tuna is exported...

In the Mediterranean basin, more than 20 countries exploit bluefin tuna, which makes it a highly shared marine resource that can only be managed within an international framework. Over the last two decades, 60% of the catches have been made by France, Spain, Italy and Japan, giving these countries a particular responsibility.

The vast majority of bluefin tuna caught in the Mediterranean by industrial fisheries is destined for aquaculture and the fattening activity that supplies the Japanese market.

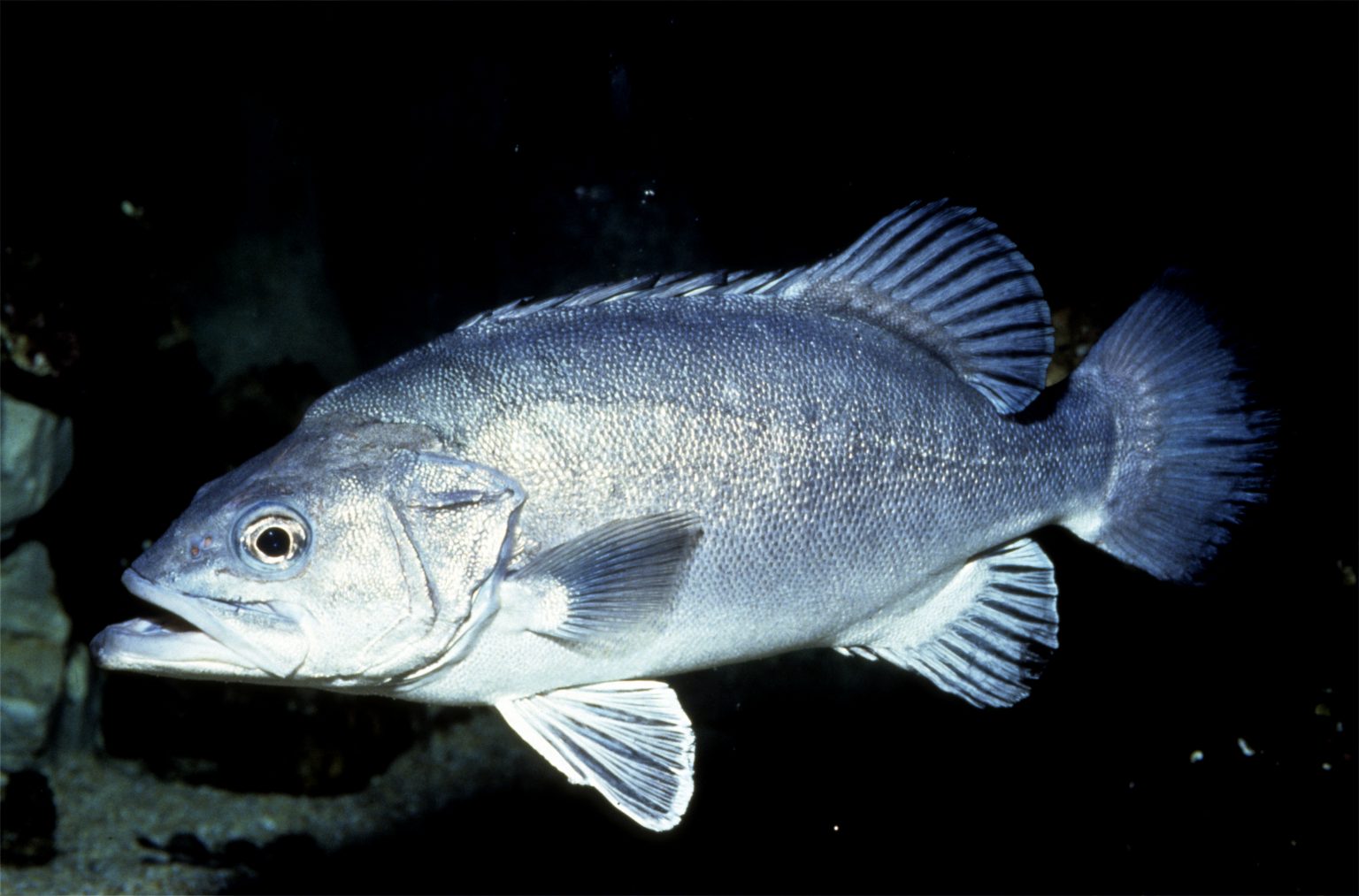

Atlantic bluefin tuna

The Atlantic bluefin tuna (Thunnus thynnus) lives in the Atlantic Ocean, the Mediterranean and the Black Sea. It moves in schools and makes important migrations to feed and reproduce. Although it tends to live in surface waters, it can dive to depths of up to 1000 m. This voracious and fast predator (it is capable of speeds of over 100 km per hour) feeds on fish, squid and pelagic crustaceans (living in open water). A record-breaking fish, it can live for 40 years or more, reach 3 m in length and weigh 600 kg! Located at the top of the marine food chain, its predators are the killer whale, the great white shark … and Man!

Read more:

Find the IFREMER press kit on bluefin tuna

Geographical distribution of bluefin tuna

This map shows the spatial distribution of the Atlantic bluefin tuna: in blue its distribution area, in yellow the known spawning areas. The black arrows indicate the main migration routes (Figure adapted from Fromentin and Powers – 2005) © Ifremer.

Did you know?

The bluefin tuna is one of the rare fish capable of endothermy: it adapts its body temperature to its environment and can thus evolve in cold water (where it feeds) or warm water (where it reproduces), that is to say from 3 to 30°C!

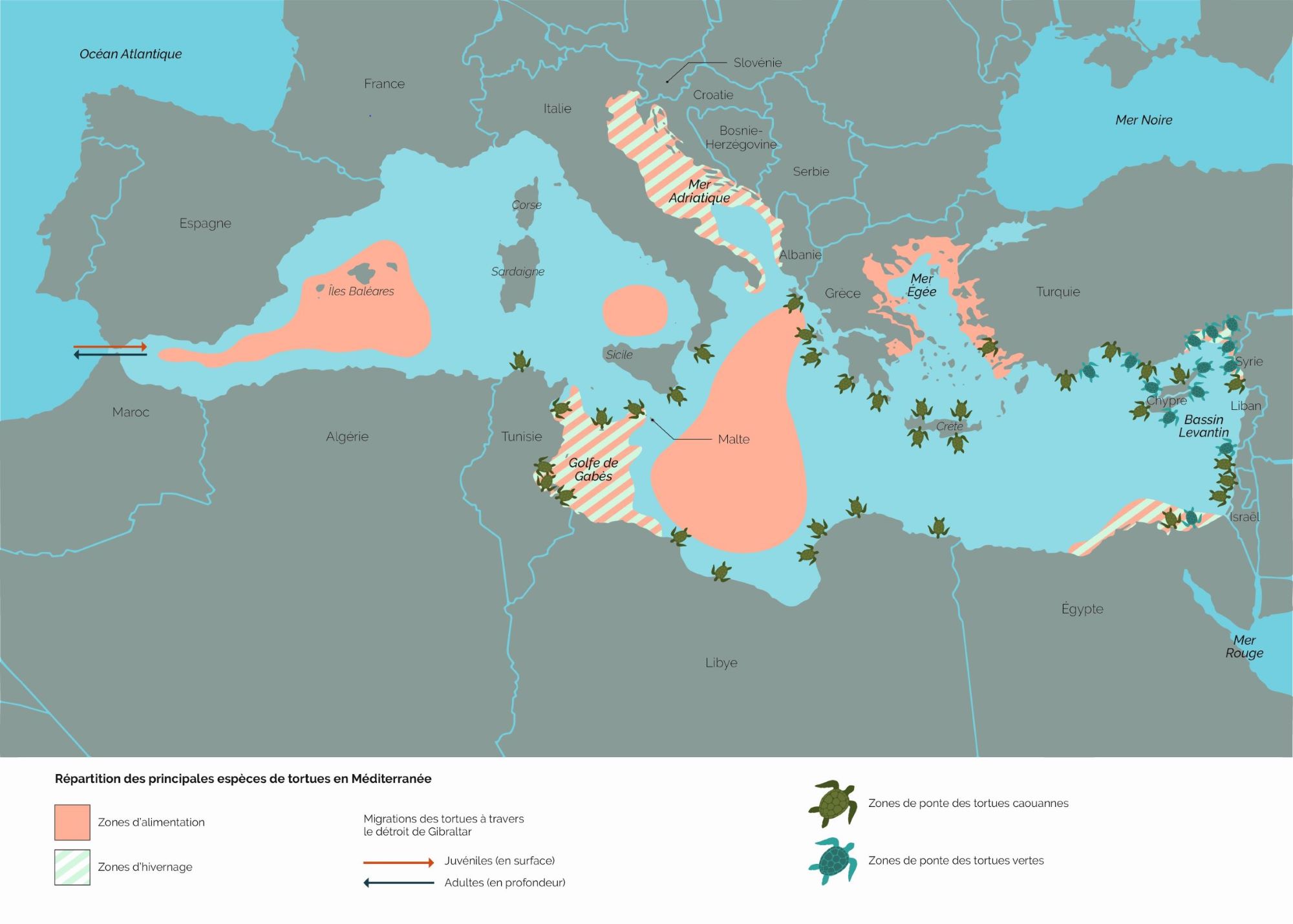

6 marine turtles are present in the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean has 46,000 km of coastline and covers 2.5 million km2 , or less than 1% of the total ocean surface. Well known as a global biodiversity hotspot, it is home to six of the seven species of marine turtles.

The loggerhead turtle Caretta caretta is the most common, followed by the green turtle Chelonia mydas and then the leatherback turtle Dermochelys coriacea, known to be the largest turtle in the world.

The rarer Kemp’s ridley turtle Lepidochelys kempii and the hawksbill turtle Eretmochelys imbricata have only been observed a few times in the Mediterranean to date.

In 2014, a stranded turtle was formally identified in Spain. It is the olive ridley turtle Lepidochelys olivacea.

An uneven geographical distribution

Loggerhead, green and leatherback turtles are found throughout the Mediterranean, but their distribution is uneven depending on the species and the time of year.

The loggerhead occupies the whole basin but seems to be more abundant in the western part, from the Alboran Sea to the Balearic Islands. It is also found off Libya, Egypt and Turkey.

The green turtle is concentrated further east, in the Levantine basin. It also appears in the Adriatic Sea and more rarely in the western part of the Mediterranean.

The leatherback turtle is observed in the open sea throughout the basin, with a more marked presence in the Tyrrhenian Sea, the Aegean Sea and around the Strait of Sicily.

Only two species breed in the the Mediterranean

The loggerhead and green turtles are the only turtles to breed in the Mediterranean, mainly in the eastern part. For the loggerhead, the sites are located in Greece, Turkey, Libya, Tunisia, Cyprus and southern Italy.

In recent years, egg-laying has been observed in the west of the basin, along the Spanish coast, in Catalonia, but also in France, in Corsica or in the Var!

In 2006, in Saint-Tropez, the nest of a loggerhead was unfortunately destroyed by heavy rain. In Fréjus in 2016, a few new hatchlings had been able to reach the sea thanks to close monitoring by teams from the French Mediterranean Sea Turtle Network (RTMMF).

In the summer of 2020, two new nests in Fréjus and Saint-Aygulf made the headlines, especially since several dozen baby turtles were born!

What do the scientists say?

From a scientific point of view, it is too early to draw conclusions on the “why” of these clutches.

Are more females nesting in this, the northernmost area for loggerheads to lay their eggs? Is there more compliance pressure from sea users? Is it a combination of several phenomena?

It’s hard to say… It seems quite clear, however, that civil society is becoming more aware of the presence of turtles and – hopefully – more concerned about the future of these fragile heritage animals.

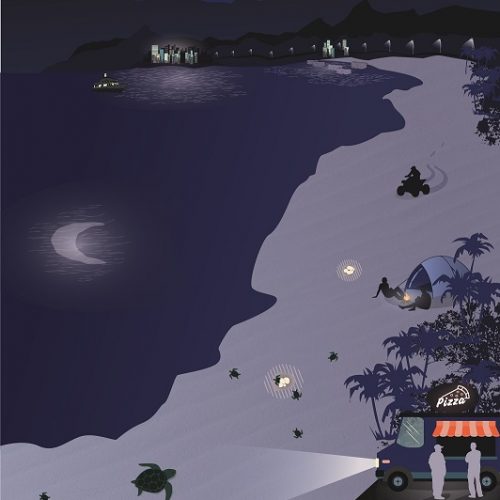

If the turtles come to lay their eggs on our beaches, it is up to us to give them some space, to create less disturbance at night and to adapt the beach lighting which can dissuade the females and disorient the juveniles.

‘Homing’, the innate ability to return home

Genetic analyses prove it: not all loggerheads observed in the Mediterranean are born there!

About half of them would be born in the Atlantic Ocean on the coasts of Florida, Georgia, Virginia or in Cabo Verde. They are born on these remote beaches, enter the Mediterranean via the Strait of Gibraltar to feed, and when they are adults, return to the beach where they were born in the Atlantic to lay their eggs.

The situation for green turtles is different. All those who live in the Mediterranean were born there. Their population is therefore genetically isolated, with no connection to other green turtle populations elsewhere in the world.

Poor genetic mixing for loggerheads

Until the end of the last great ice age, 12,000 years ago, the cold climatic conditions in the Mediterranean did not allow loggerhead turtles to settle or feed, let alone reproduce .

Incubation of eggs is only possible if a temperature of 25°C is maintained for a minimum of 60 days. It was only when temperatures stabilized at levels close to present-day climatology that the Atlantic loggerhead turtles, which had remained in warmer areas during the ice age, were able to colonize the Mediterranean.

Their presence in the Mediterranean is therefore – relatively – recent.

How many turtles in the Mediterranean?

This is a difficult question to answer! There is no technological way to count all the marine turtles present in such a large maritime area, especially as these great migrants are constantly moving from one area to another.

Knowing the abundance of turtles is a priority in scientific research aimed at conserving marine turtles in the Mediterranean. This is one of the many conclusions of the recent IUCN report, which also gives some estimates: there are between 1.2 and 2.4 million loggerhead turtles in the Mediterranean and green turtles are estimated to be between 262,000 and 1,300,000; extremely wide ranges due to the difficulty of conducting censuses.

While counting individuals at sea is illusory, it is possible to monitor the number of females coming to lay eggs, beach by beach, year after year. Nearly 2,000 loggerheads come ashore to lay eggs, mainly in the Levantine basin (Greece, Turkey, Cyprus and Libya).

Good news, the number of clutches is increasing! On about twenty reference sites, the annual average has increased from 3,693 nests per year before 1999 to 4,667 after 2000, an increase of over 26%! The same goes for green turtles. At 7 reference sites in Cyprus and Turkey, the annual average number of nests increased from 683 to 1,005 between before 1999 and after 2000, i.e. + 47%!

These very positive trends show that conservation efforts are paying off and deserve to be continued and expanded.

What does the IUCN say about Mediterranean turtles?

This new report sheds new light on the key nesting, feeding and hibernation sites of Mediterranean turtles.

It also proposes a series of recommendations and actions at the basin level for managers, policy makers and the general public.

This new report sheds new light on the key nesting, feeding and hibernation sites of Mediterranean turtles.

It also proposes a series of recommendations and actions at the basin level for managers, policy makers and the general public.

Priorities include:

- Strengthen monitoring and protection of nesting areas

- Conserve priority feeding and hibernation areas (e.g. through Marine Protected Areas) and preserve seasonal migration corridors

- Reduce by-catches by adapting fishing techniques and training fishermen in the proper way to release caught specimens

- Fight against all forms of pollution

- Strengthen the protection networks by actively involving every actor in society (marine professional, fisherman, conservation expert, researcher, political decision-maker or ordinary citizen)

- Improve the network of rescue and relief centres, which are currently too unevenly distributed and virtually absent from the southern and eastern shores of the Mediterranean.

Some coral species are being studied to better understand calcification or the spread of disease, while others are being studied for their molecules that protect against sunlight or aging. Corals are the basis of many research projects to find tomorrow’s drugs or cosmetics or to understand how certain diseases are formed.

Coral reefs have an important ecological role. Often in waters that are not very rich in phytoplankton, the source of the marine food chain, they offer real oases of life in the middle of the oceanic desert. They also provide an ideal natural barrier against cyclones, storms and erosion as they absorb the power of the waves.

Coral reefs: an oasis of life

Although they cover barely 0. 2% of the ocean’s surface, coral reefs are home to 30% of marine biodiversity! For fish and other marine animals, corals are real shelters against predators, but also a reproduction and nursery area for many species. They are the essential foundation of marine life in the tropics.

Coral reefs provide direct sustenance to 500 million people worldwide through fishing, and reefs protect coastlines more effectively than any man-made structure from swells and tsunamis.

Read more:

- Coral reefs by Jean Jaubert, marine biologist and former director of the Oceanographic Museum

A major asset for tourism

They are a major tourist attraction and generate a significant part of the economic income of the tropical regions where they are found. Annual net profits of several million or even billion euros per year. Australia, Indonesia, the Philippines, more than a hundred countries benefit from this ” reef tourism “.

Medical Perspectives

Humans and corals have a common genetic heritage. Studying coral and the molecules they produce offers many prospects for human and animal health. The genome, the genetic material of the Acropora coral, has 48% correspondence with that of a human being. While the latter shares only 8% of correspondences with Drosophila, a fly used by laboratories as a model for genetic work! This represents incredible prospects for medical research!

Read more:

- Coral reefs by Jean Jaubert, marine biologist and former director of the Oceanographic Museum

- Why don’t corals get sunburned? by John Malcolm Shick, Professor of Zoology and Oceanography

- Why don’t Corals Get sunburned? by John Malcolm Shick, Professor of Zoology and Oceanography

- The Institute’s coral sheets

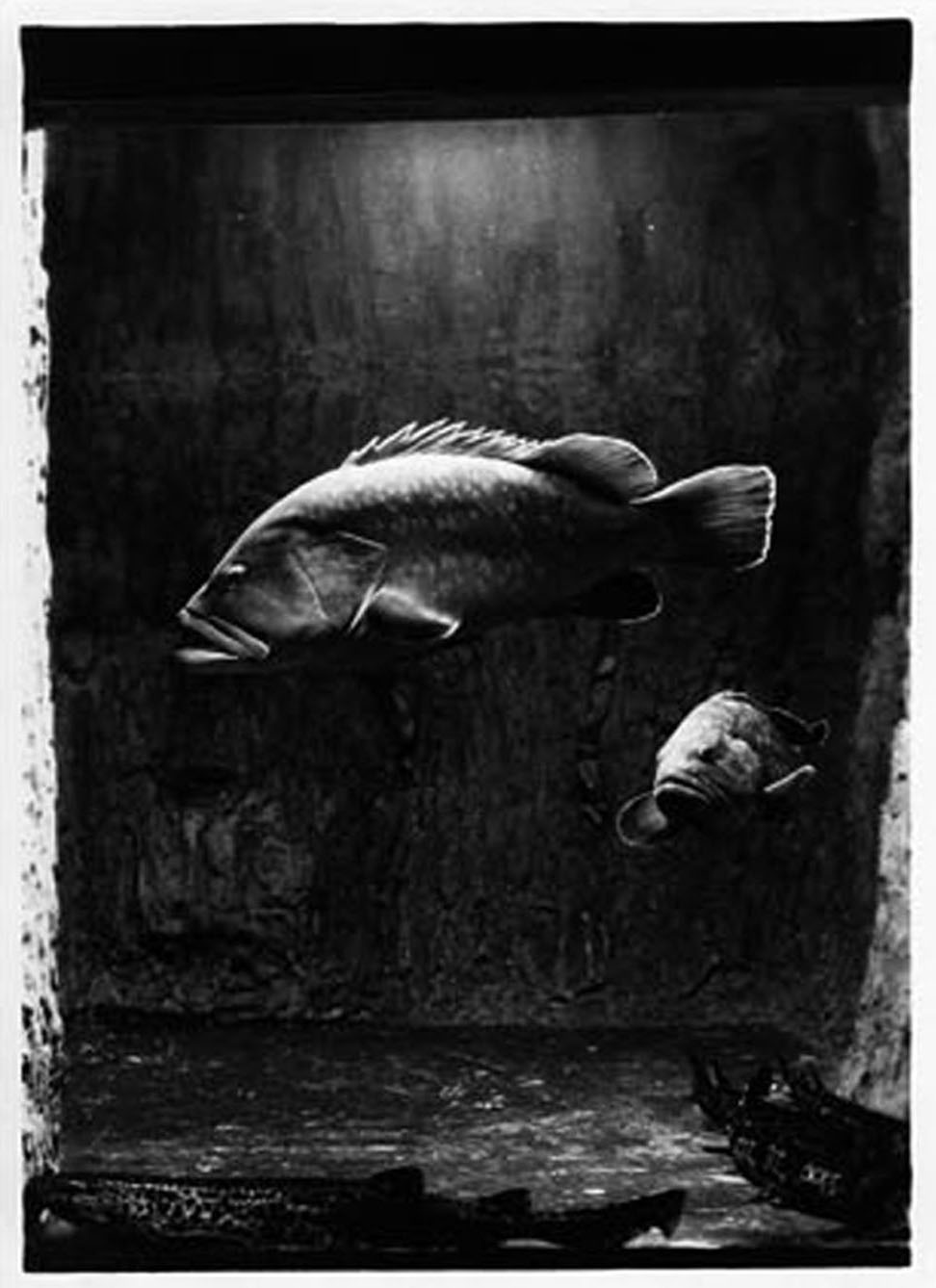

Back on our shores after 30 years of effort

An icon for many scuba divers, both for its size (it is one of the largest bony fish in the Mediterranean) and its rarity, the brown grouper Epinephelus marginatus had almost disappeared after decades of overfishing and poaching. Thanks to strong protection measures, it is making a strong comeback in the waters of the French and Monegasque Mediterranean, especially in protected areas, allowing the underwater hiker to admire its unique and majestic behaviour. Watching it while diving is a privileged and magical moment, a memory that you will keep in your head for a long time! The return of the grouper is not a coincidence but the result of 30 years of efforts, an example that should inspire us to better protect endangered species in the Mediterranean! Explanations…

Male or female? Both of them! A little biology...

The brown grouper lives between the surface and 50 to 200m depth, in the Atlantic Ocean (from the Moroccan coasts to Brittany) as well as in the whole Mediterranean Sea. It is also found off Brazil and South Africa, but researchers wonder if it is a homogeneous population or distinct subpopulations. The mystery remains today!

It likes coastal rocky habitats rich in crevices and cavities. The juveniles, more littoral, are sometimes observed in a few centimeters of water. Its size varies from 80 cm to 1 m or even 1.5 m for the largest individuals.

The grouper changes sex during its life: “protogynous hermaphrodite”, it is first female then becomes male when it reaches 60 to 70 cm, at the age of 10 to 14 years.

Regulator and indicator of the state of the marine environment

A super-predator at the top of the food chain, the grouper hunts its prey (cephalopods, crustaceans, fish) at lower trophic levels, thus playing the role of regulator and contributing to the balance of the ecosystem. It is also an indicator of environmental quality. The abundance of groupers reflects the good condition of the food chain that precedes it, the presence of rich food and the expression of moderate poaching and fishing pressure. Because of its very high commercial value, the brown grouper remains highly sought after by fishermen and underwater hunters throughout its distribution area. Its numbers are in sharp decline and it is classified by the International Union for Conservation of Nature as a vulnerable species.

Did you know?

8 species of groupers are present in the Mediterranean. Among the 6 species observed in Monaco, the brown grouper Epinephelus marginatus is the most frequent, then comes the impressive cernier, still called wreck grouper Polyprion americanus. The canine grouper Epinephelus caninus, the badèche Epinephelus costae, the white grouper Epinephelus aeneus, the royal grouper Mycteroperca rubra are much more discrete.

Grouper protection works!

The rarefaction of this fish has led France and the Principality of Monaco to adopt strong protection measures within the framework of international conventions (Bern, Barcelona). The moratorium set up in continental France and in Corsica since 1993 prohibits underwater hunting and fishing with hooks. Field studies show the effectiveness of these protection measures: young groupers are now present on all the coasts, and in the marine reserves the populations have recovered. But this comeback remains very fragile. The moratorium is to be reviewed every 10 years. The future of the grouper will therefore be decided in 2023. If hunting were to be allowed again, more than 30 years of effort could be wiped out in a few weeks!

In Monaco, the Sovereign Order of 1993, reinforced by theOrder of 2011, prohibits all fishing and ensures the protection of the brown grouper as well as the corb, another vulnerable species. Thanks to this specific protection, to the Larvotto Reserve and to the presence of very favourable habitats and abundant food, the brown grouper is once again abundant in the waters of the Principality of Monaco, particularly at the foot of the Oceanographic Museum.

Did you know?

Why do we still find brown groupers on the fishmongers’ shelves? Simply because the use of nets to catch them is still allowed. Specimens imported from unregulated areas may also be offered for sale. It is up to us as consumers to avoid buying endangered species!

The principality takes care of the groupers

Since 1993, under the control of the Environment Department, the Monegasque Association for the Protection of Nature, assisted by the Grouper Study Group, has been carrying out a regular inventory of groupers in Monegasque waters, from the surface to a depth of 40 m, with the natural participation of divers from the Oceanographic Museum. From year to year, the numbers observed increase (15 individuals in 1993, 12 in 1998, 83 in 2006, 105 in 2009, 75 in 2012). Large specimens of 1.40 m are now numerous and juveniles of all sizes are observed on the shallows.

The Oceanographic Museum also gets wet...

The Museum also comes to the rescue of specimens in difficulty that are entrusted to it by fishermen or divers, as was the case at the end of 2018, with several individuals affected by a viral infection, already observed in the past on several occasions in the Mediterranean in Crete, Libya, Malta, and Corsica. With the Monegasque Marine Species Care Centre created in 2019 to care for turtles and other species, these interventions are now facilitated. The cured groupers return to the sea to be in protected areas such as the Larvotto Underwater Reserve. Watch the video of the release of the young grouper “Enzo”.

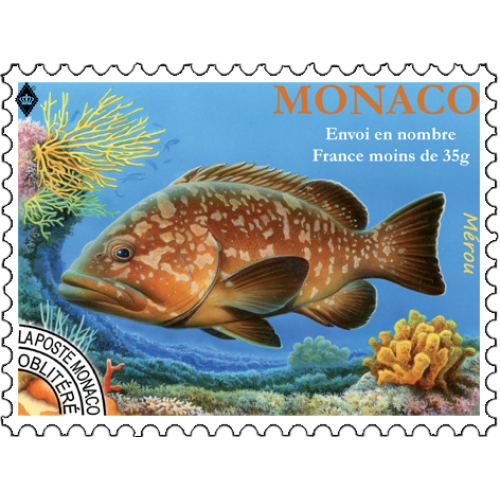

The merou, a long-time star at the aquarium

Many visitors discover this heritage species at the Oceanographic Museum. This is not new, since the Aquarium, then directed by Doctor Miroslav Oxner, was already presenting them in 1920! One of them, now kept in the Museum’s collections, lived there for more than 29 years. Four different species (badèche, brown, white and royal grouper) can now be seen in the completely renovated section dedicated to the Mediterranean.

If the grouper intrigues visitors, it also inspires artists! Numerous objects bearing his likeness, both works of art and manufactured objects, can be found in the collections of the Oceanographic Institute!

In 2010, a grouper from the Museum was used as a model for the 100 Reais banknote issued by the Central Bank of Brazil, which is still in circulation today, and the Principality even dedicated a postage stamp to it in 2018!

An asset for the blue economy, tourism and fishing...

Tourists come from far and wide to observe the underwater fauna and a “successful” dive is often one during which the brown grouper has been observed! Several studies show that a live grouper brings in infinitely more money during its existence than if it is caught to be consumed!

Brown grouper particularly thrive in effectively managed marine protected areas (MPAs), which provide important biodiversity conservation and economic development benefits. By protecting and restoring critical habitats (migration routes, predator refuges, spawning grounds, nursery areas), MPAs contribute to the survival of sensitive species such as brown grouper. Adults and larvae of different species living within an MPA can also leave and colonise other areas, a process known as spillover. When eggs and larvae produced within the MPA drift outside, this is called Dispersal. Species with a high market value (brown grouper, lobster, red coral) travel considerable distances, providing ecological and economic benefits in remote areas! Adult brown groupers stray one kilometre outside the MPA boundary. As for the larvae, they travel several hundred killometers!

A delimited space at sea

A Marine Protected Area (or MPA) is a delimited area at sea that meets the objectives of nature protection (fauna, flora, ecosystems) and the sustainable development of economic activities such as sustainable fishing and responsible tourism.

Formed into effectively designed and managed networks, MPAs provide refuges for marine flora and fauna, restore important ecological functions (e.g. safeguarding spawning grounds and fish nursery areas) and maintain the production of ecosystem goods and services. These are wise investments for the health of the oceans and the development of the blue economy.

Data as of 27.04.20. Source

The answer is yes! There are several thousand whales living in the waters of the Mediterranean. It is even not uncommon to see their breath from far away, on crossings to Corsica, for example. But beware: human activities are a source of disturbance for these giant mammals. It is therefore very important to do everything possible to preserve their peace of mind.

There are nearly twenty species of marine mammals in the Mediterranean, eight of which are considered common: sperm whales and fin whales, of course, but also dolphins (common, blue and white, Risso’s, bottlenose dolphin), pilot whales and ziphiuses. Other species are observed on a very occasional basis such as the minke whale, the killer whale, the humpback whale and very recently a young grey whale!

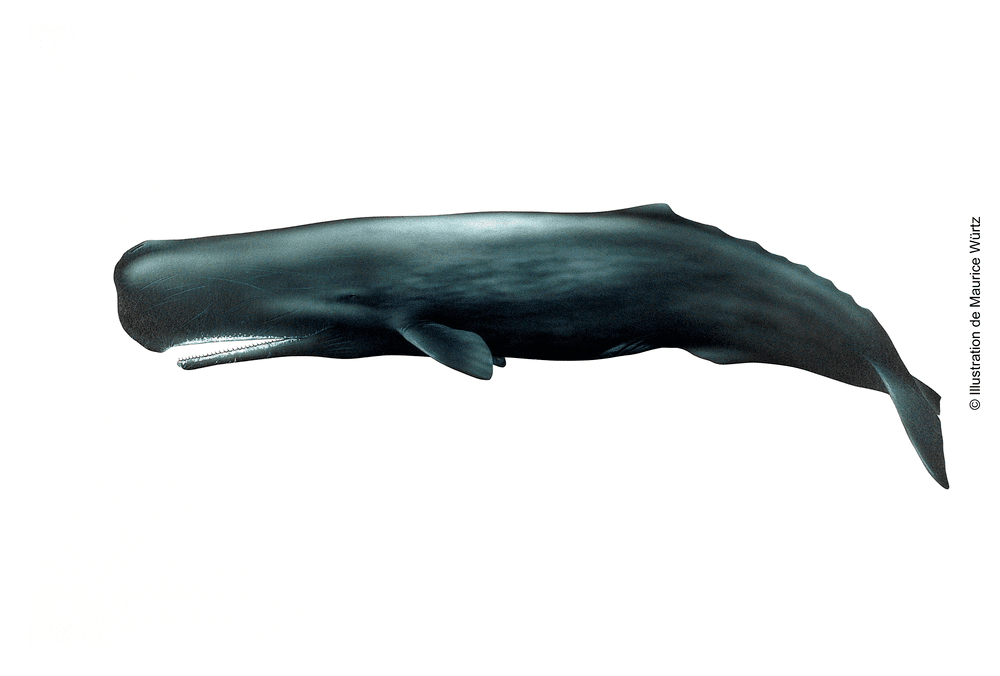

Sperm whale Physeter catodon

Baleen or teeth?

In common parlance, we tend to refer to all large cetaceans as “whales”. However, only “baleen whales” (mysticetes) are really whales.

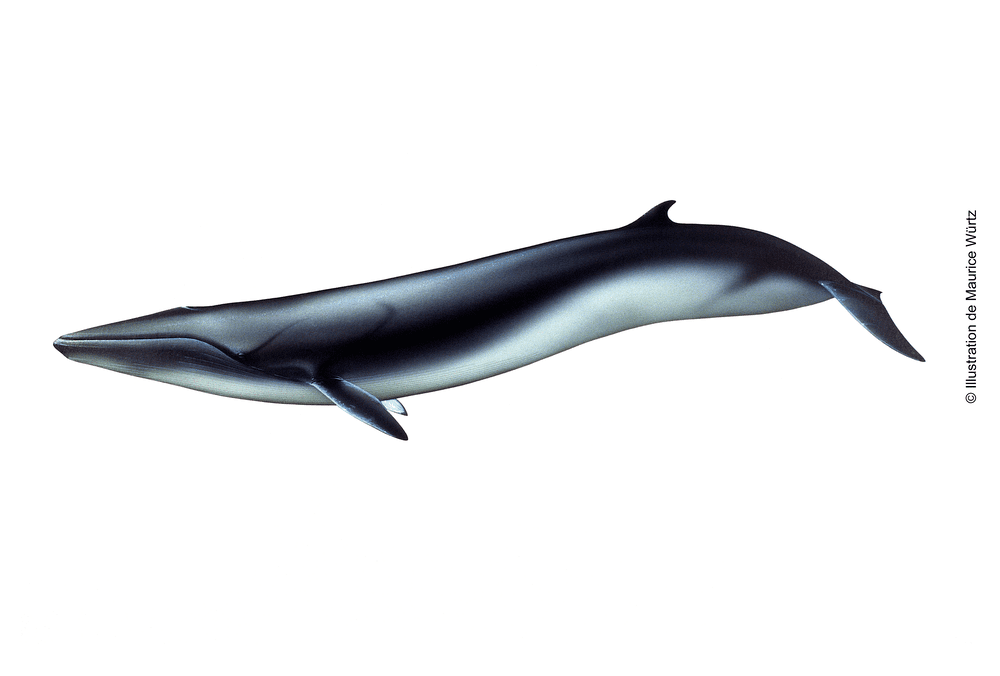

The fin whale (up to 22 metres and 70 tonnes) is the main baleen whale in the Mediterranean.

It rubs shoulders with numerous “toothed cetaceans” (odontocetes), the largest of which is the sperm whale (up to 18 metres and 40 tonnes).

Despite its imposing stature, this whale is not strictly speaking a whale, and belongs to the same group as orcas, dolphins or pilot whales.

A giant of the seas

The fin whale is the second largest mammal in the world, just behind the blue whale!

Although it is still difficult to assess the exact size of its population (as individuals are constantly on the move and dive regularly), it is estimated that about a thousand individuals live in the protected area of the Pelagos Sanctuary, which aims to protect marine mammals in the western Mediterranean over a vast territory including French, Italian and Monegasque waters.

The fin whale feeds mainly on krill, small shrimp that it traps in its baleen plates in large quantities.

Fin whale Balaenoptera physalus

Risk of collision

Fin whales can live up to 80 years, if their trajectory does not meet that of the fast ships that are common in summer, which they find difficult to avoid when breathing on the surface.

As for sperm whales, collisions are a real danger and a proven risk of mortality. Hence the interest in developing techniques in partnership with shipping companies to inform ships of the presence of cetaceans in real time, to equip ships with detectors and thus prevent collisions with these large mammals.

Discover the different species of marine mammals in the Pelagos Sanctuary.