6 marine turtles are present in the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean has 46,000 km of coastline and covers 2.5 million km2 , or less than 1% of the total ocean surface. Well known as a global biodiversity hotspot, it is home to six of the seven species of marine turtles.

The loggerhead turtle Caretta caretta is the most common, followed by the green turtle Chelonia mydas and then the leatherback turtle Dermochelys coriacea, known to be the largest turtle in the world.

The rarer Kemp’s ridley turtle Lepidochelys kempii and the hawksbill turtle Eretmochelys imbricata have only been observed a few times in the Mediterranean to date.

In 2014, a stranded turtle was formally identified in Spain. It is the olive ridley turtle Lepidochelys olivacea.

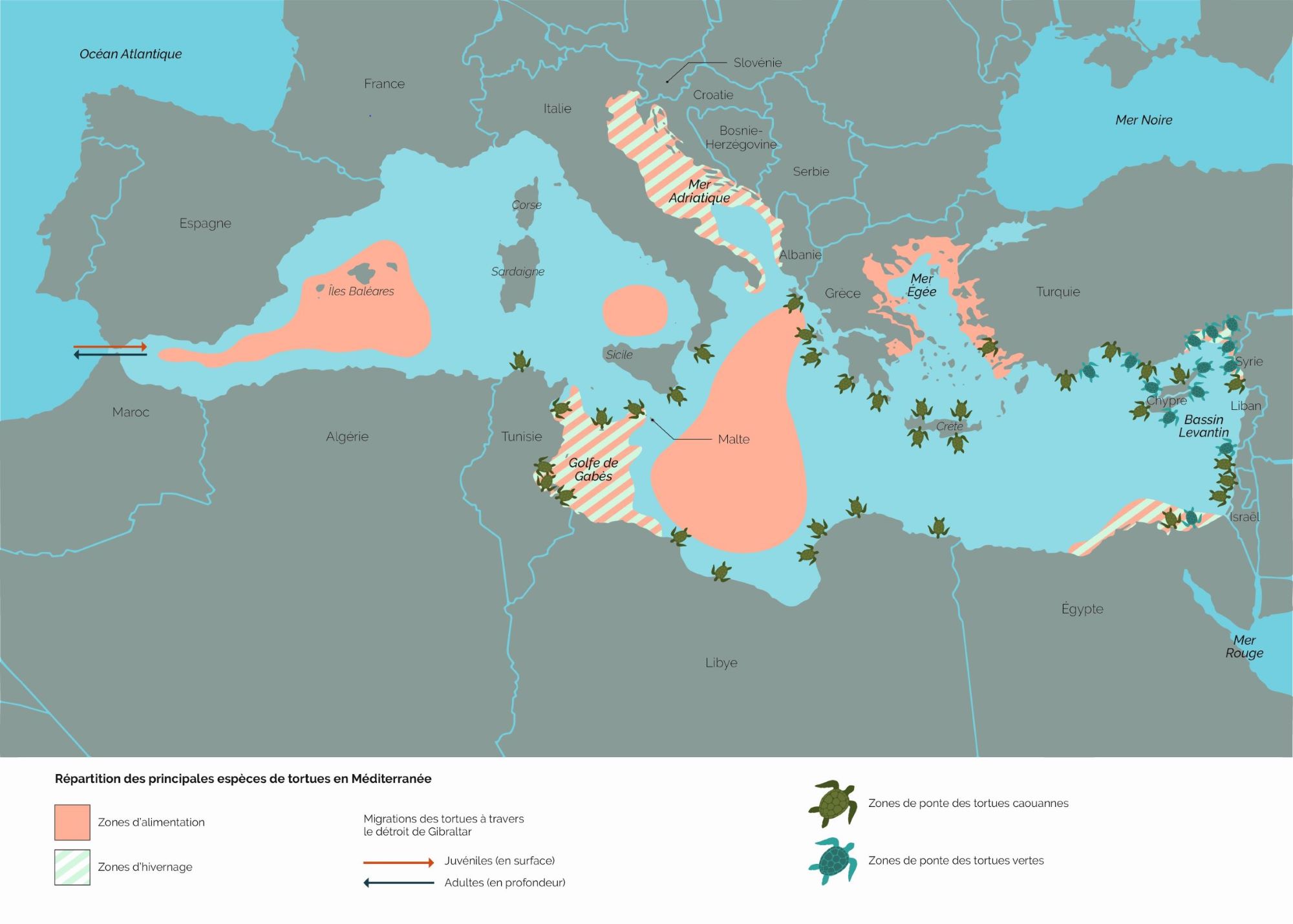

An uneven geographical distribution

Loggerhead, green and leatherback turtles are found throughout the Mediterranean, but their distribution is uneven depending on the species and the time of year.

The loggerhead occupies the whole basin but seems to be more abundant in the western part, from the Alboran Sea to the Balearic Islands. It is also found off Libya, Egypt and Turkey.

The green turtle is concentrated further east, in the Levantine basin. It also appears in the Adriatic Sea and more rarely in the western part of the Mediterranean.

The leatherback turtle is observed in the open sea throughout the basin, with a more marked presence in the Tyrrhenian Sea, the Aegean Sea and around the Strait of Sicily.

Only two species breed in the the Mediterranean

The loggerhead and green turtles are the only turtles to breed in the Mediterranean, mainly in the eastern part. For the loggerhead, the sites are located in Greece, Turkey, Libya, Tunisia, Cyprus and southern Italy.

In recent years, egg-laying has been observed in the west of the basin, along the Spanish coast, in Catalonia, but also in France, in Corsica or in the Var!

In 2006, in Saint-Tropez, the nest of a loggerhead was unfortunately destroyed by heavy rain. In Fréjus in 2016, a few new hatchlings had been able to reach the sea thanks to close monitoring by teams from the French Mediterranean Sea Turtle Network (RTMMF).

In the summer of 2020, two new nests in Fréjus and Saint-Aygulf made the headlines, especially since several dozen baby turtles were born!

What do the scientists say?

From a scientific point of view, it is too early to draw conclusions on the “why” of these clutches.

Are more females nesting in this, the northernmost area for loggerheads to lay their eggs? Is there more compliance pressure from sea users? Is it a combination of several phenomena?

It’s hard to say… It seems quite clear, however, that civil society is becoming more aware of the presence of turtles and – hopefully – more concerned about the future of these fragile heritage animals.

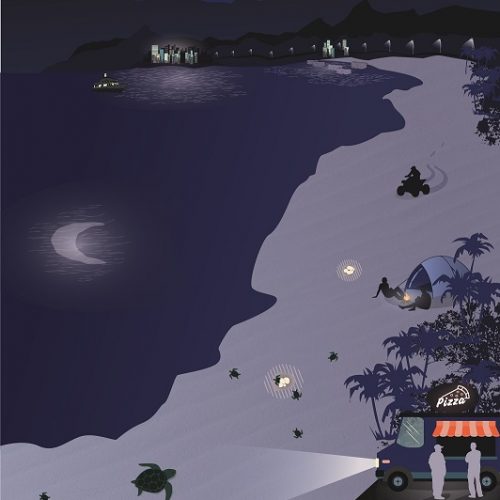

If the turtles come to lay their eggs on our beaches, it is up to us to give them some space, to create less disturbance at night and to adapt the beach lighting which can dissuade the females and disorient the juveniles.

‘Homing’, the innate ability to return home

Genetic analyses prove it: not all loggerheads observed in the Mediterranean are born there!

About half of them would be born in the Atlantic Ocean on the coasts of Florida, Georgia, Virginia or in Cabo Verde. They are born on these remote beaches, enter the Mediterranean via the Strait of Gibraltar to feed, and when they are adults, return to the beach where they were born in the Atlantic to lay their eggs.

The situation for green turtles is different. All those who live in the Mediterranean were born there. Their population is therefore genetically isolated, with no connection to other green turtle populations elsewhere in the world.

Poor genetic mixing for loggerheads

Until the end of the last great ice age, 12,000 years ago, the cold climatic conditions in the Mediterranean did not allow loggerhead turtles to settle or feed, let alone reproduce .

Incubation of eggs is only possible if a temperature of 25°C is maintained for a minimum of 60 days. It was only when temperatures stabilized at levels close to present-day climatology that the Atlantic loggerhead turtles, which had remained in warmer areas during the ice age, were able to colonize the Mediterranean.

Their presence in the Mediterranean is therefore – relatively – recent.

How many turtles in the Mediterranean?

This is a difficult question to answer! There is no technological way to count all the marine turtles present in such a large maritime area, especially as these great migrants are constantly moving from one area to another.

Knowing the abundance of turtles is a priority in scientific research aimed at conserving marine turtles in the Mediterranean. This is one of the many conclusions of the recent IUCN report, which also gives some estimates: there are between 1.2 and 2.4 million loggerhead turtles in the Mediterranean and green turtles are estimated to be between 262,000 and 1,300,000; extremely wide ranges due to the difficulty of conducting censuses.

While counting individuals at sea is illusory, it is possible to monitor the number of females coming to lay eggs, beach by beach, year after year. Nearly 2,000 loggerheads come ashore to lay eggs, mainly in the Levantine basin (Greece, Turkey, Cyprus and Libya).

Good news, the number of clutches is increasing! On about twenty reference sites, the annual average has increased from 3,693 nests per year before 1999 to 4,667 after 2000, an increase of over 26%! The same goes for green turtles. At 7 reference sites in Cyprus and Turkey, the annual average number of nests increased from 683 to 1,005 between before 1999 and after 2000, i.e. + 47%!

These very positive trends show that conservation efforts are paying off and deserve to be continued and expanded.

What does the IUCN say about Mediterranean turtles?

This new report sheds new light on the key nesting, feeding and hibernation sites of Mediterranean turtles.

It also proposes a series of recommendations and actions at the basin level for managers, policy makers and the general public.

This new report sheds new light on the key nesting, feeding and hibernation sites of Mediterranean turtles.

It also proposes a series of recommendations and actions at the basin level for managers, policy makers and the general public.

Priorities include:

- Strengthen monitoring and protection of nesting areas

- Conserve priority feeding and hibernation areas (e.g. through Marine Protected Areas) and preserve seasonal migration corridors

- Reduce by-catches by adapting fishing techniques and training fishermen in the proper way to release caught specimens

- Fight against all forms of pollution

- Strengthen the protection networks by actively involving every actor in society (marine professional, fisherman, conservation expert, researcher, political decision-maker or ordinary citizen)

- Improve the network of rescue and relief centres, which are currently too unevenly distributed and virtually absent from the southern and eastern shores of the Mediterranean.